Palestinian Education: British Mandatory Era (1917-47)

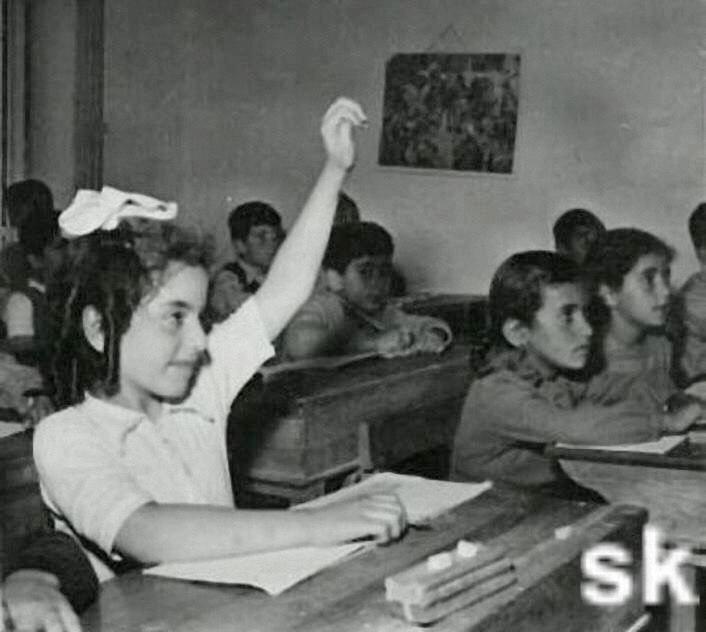

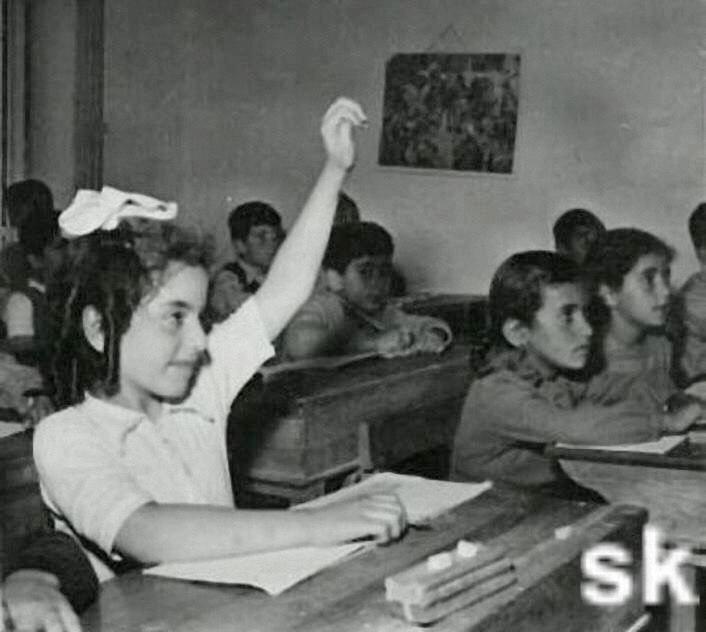

Figure 1.--A Palestinian source provides us this pohotograph, described as a school in Lod during 1940. Lod was a mixed Jewish-Arab cuty in westrern central Palestine. There is no indication as to whether it is an Arab public school o a millet school. We think it is may be a Jewish school because it is a coed class. That was not unusal in village schools, but was less common in city schools. Also I am not sure Arab Muslim girls cmmninly had ringlet curls. Perhaps readers have some insight.

|

|

The British inherited the three tier system establised by the Ottoman Empire: muslim public schools, mosque schools, and millet schools. The basically continued this system. The Mandate public schools were attended by Arab Muslim students, but were largely secular. The British massively expanded Arab Muslim education, opening schools in villages that never had schools before. Most boys attended school for the first time. And the education of girls was even more significantly expanded. Mosque education continued, but educated only a small number of children and only boys. The millet (Christians and Jews) schools continued. Under the Mandate system these were private schools, but received Government financial support. Unlike America, this is not unusual. The Governments in many countries provide financial support to schools supported by faith based communities. Education was a well-established tradition in both communities. Thus the expansion of education was less dramatic than with the case of Arab Muslim children. But the increased resources devoted to education meant that both the millet systems benefitted and expanded. The Brirish possibly could have theoretically created on comprehensive educational system, but given the communal, religious, and cultural differences, there is little doubt that there would have been enfless problems trying to mix the children together.

While Arab authors are uniformily critical of the British role in Palestine, in fact the British took their responsibilities very seriously and put an emphasis on eucation on education that the Ottomons never did and for the first time made Arabic the language of education for Arab children. The British helped finance the opening of mny new schools, including village schools. Th ttoman schools were almost all located in cities and towns. An Arab author critical of the British has to admit, "What is particularly striking about the Arab schooling system under the British Mandate is the extent of its quantitative increase. Also, the British Mandate authorities seemed to allow the original owners of Arab schools to maintain their control over their schools." [Jabareen] Under the Brtish, education was free, but not compulsory. The Ottoman public school system at the end of the War included some 100 schools. Under the British the number of schools increased to 550 (1947). Under the Ottomans only about 5 percent of the children attended school. the British raised this to more than 30 percent. The primary constraint was not the lack od schools, but the reluctance of Muslim Arab parents to send their girls to school. Of course if the British had tried to make public school attendance compulsory their would have been a unroar of opposition among Aran parents and cgarges of oppresive colonial rule. A fair assessment of the British achievment reports, "Overall, Arab education in Palestine developed significantly under the Mandatory administration. Schools were established in many villages, making educational opportunities more accessible. Secondary school education increased and became strongly associated with the achievement of a white collar job, usually as a clerk or a civil servant who not only enjoyed economic mobility and security, but also a higher status due to his [note the male form] association with the rulers." [Mar’i, p. 15.]

Mosque schools (kuttab) and private education until late in the Ottoman era was how eas how Muslim Arab boys were educted. These schools wwre small and not free so the number of children educated were very small and were only boys. Even when the Ottomans began opening public schools (late-19th century), the Mosque schools continued to operate, but still educated only a small number of children and only boys. There was obviously a focus on religion, primarily commiting the Koran to memory. Many of the boys learned to read, but not necessarily to write. We believe that Mosque schools continue to operate during the mandate. One sources suggesta that they were incorporated into the Mandate system. [Talhami, p. 364.] Some may have been, but the Mosque schools were under the authority of the Supreme Muslim Council which controlled the Islamic awqaf which included independent financial resources. Also part of the awqaf were the sharia courts, and officiadom, moaques, orpgnages and other Islamic institutions. [Farsoun and Aruri, p. 86.] We note mosque schools still operating still operating during the mandate. Perhaps the source meant that they received some government support. At any rate the numbers of boys educated at these schools were relatively small. We are not sure if the Mandate authories regulated these schools in any ways. We suspect that many boys planning to be Muslim clerics attended these schools rather than the Mandate public schools.

Millet Schools

The Ottoman Empire maintained separate courts of law for individuals belonging to faith based communities. These were called millets. These courts addressed what was seen as 'personal' law, matters like marriage, inheritance, commercial contracts, intra-communal crime, and other matters. Confessional communites (groups abiding by Muslim Sharia, Christian Canon law, or Jewish Halakha) were allowed to govern themselves under their own laws. Many authors refer to this as rhe 'millet system'. Other maintain that Ottoman millet administration was far from systematic. Rather it is probanly better described as giving non-Muslims a substantial degree of autonomy within their own communities, but there was not real imperial structure for the 'millet' as a whole. This seems to have been a kind of haphazzard development as the Ottomans cinquered non-Turkish and non-Muslim peoples. Late in the Ottoman, the Tanzimat Reforms (1839–76) used the term millet for legally protected religious minority groups, in the sence other countries might use the term nationlity. Indeed the word comes from the Arabic word millah (ملة) literally meaning 'nation'. In this sence the millet system can be seen as example of pre-modern religious pluralism. [Sachedina, pp. 96–97.] This was sorely lacking in Christian Europe, but after the gastly 17th century religious wars was begging to develop in the 18h century Enligtenment. Unfortunately by the 19th century, the Ottomans and Arabs were moving in avery different sirection. Education was one area which the Ottomans saw as falling under the millet system, in part because as the millet system was developing there was not national Ottoman educational system or interest in building one. Thus it as left to the millet communities to eal with education. The Ottomans only with the Tanzimat reforms made any serious effort yo establish a public school system.

This is what the British inherited in 1918. And the Christian and Jewish Millet schools were part of that system.

Christian schools

Jewish schools

The Jewish schools in Palestine were private schools. Following British tradition, the Mandate authotities made little effort to interfere with these schools. This had the added advantage that they did not have to assume all of the financial responsibility for supporting these schools. Unlike the Ottomans They did provide a block grant. We are not sure about the amount or how it compared to the funding for the Arab public schools. An Arab author complains, "Unlike the education system of the Palestinian Arabs, the Jewish educational system always moved towards further autonomy and independence." The major role of the British in Plistinian Aab schools of course was to massively increase the number of schools and number of children atending the schools. The number of Jews in Palestine increased 24,000 in 1882 to 60,000 in 1918 when the British seized Palestine. The numbers had reached 650,000 by the end of the Mandate (1948). Among the

80,000 Jews who lived in Ottoman Palestine during 1914 when the Ottoman Empire declare war on Britain, some 12,000 lived in 44 different kibbutzes (agricultural settlements). Until this time the Arab and Jewish communities had lived in general harmony. This changed during the War. Ottoman policy toward the Jews changed dramatically, viewing them as a British ally. This also affected Arab attitudes which became increasingly nationlistic with the aran Revolt in the Hejab. Many Jews fled Palestine. Those that remaied experienced arrest, torture, mistreatment, and famine. This was the beginning of the acrimonious Arab-Jewish conflict. The Jews began for the first time to think about self defense. This was the situation when the British arrived in Palestine. One historian writes, "Thus, from the outset, there arose bitter controversy among the British, Arabs and Jews concerning the relative weight that was to be assigned to the conflicting purposes of the Mandate." [Kleinberger, p. 15.] The education system was one of the important issues in this developing conflict. The same historin continues, "Under these circumstances, the Jewish community in Palestine was driven to rely more and more on its own autonomous institutions which constituted a veritable state within the state." [Kleinberger, p. 20.] Few undertakings are more central to Jewish life than education. Here Arab and Jewish thinking was very different. The principl Zionist parties moved to establish control over the

developing Jewish education system. The result was the 'trend' system. The different parties sought to ensure that the parties sought to ensure that educational philosophies and programs of the schools they ponsored reflected the party outlook. [Abraham, p. 10.] There was considerable ideological division among the parties even within the Zionist community. The biggest gulf was that between the religious and the socialist parties. And as the Jewish community expanded, the more sophisticated and diverse the schools became. An historian reports, "New kinds of schools and institutions appeared, 'financed and maintained by Jewish philanthropic and Zionist organizations

the world over'. [Abraham, p. 16.] The Jewish community achieved considerable economic prosperity with social and economic achievements during the Mandate erawhile the Arab comminity, especially Muslim Arabs made only limited gains. And this was during a period of great pressure on world Jewery because of the rise of Fascism in Europe, especlly the NAZIs in Europe. A major cintribution to the success of Jews in Palestine was the development of the Jewish school system. [Avidor, p. 21.] In contrast to the Muslim-Arab commuity, the Jews required compulsory school attendance from the beginning. Jews in Palestine were aided by foreign Jewish communities, but Palestinian Jews made great scarifices to build a school system with high standards. One historian rports, "the community

imposed substantial taxation upon itself and demanded tuition fees from parents in order to maintain its education system." [Avidor, p. 22.] Parents paid a substantial portion of the cost of educating their children. The Jews began building. Since the early-20th century, the Jewish community suceeding in estanlish a substantial school systems with European stndards. The Jewish community did this on their own with virtually no suppot from the Mandatory Governemrnt, except that they were left alone.

Sources

Avidor, Moshe. Education in Israel (Jerusalem: 1958).

Farsoun, Samih K. and Naseer Aruri. Palestine and the Palestinians: A Social and Political History (Avalon Publishing: 2006), 488p.

(Al-) Hag, Majid. Education, Empowerment, and Control: The Case of the Arabs in Israel (State University of New York Press: 1995).

Jabareen, Alu. "The Palestinian Education system in Mandatory Palestine".

Kleinberger, Aharon. Society, Schools and Progress in Israel (Pergamos Press: 1969).

Mar’i, Sami Khalil. Arab Education in Israel (Syracuse University Press: 1978).

Sachedina, Abdulaziz Abdulhussein. The Islamic Roots of Democratic Pluralism (Oxford University Press: 2001)

Talhami, Ghada Hashem, "Palestinian governance: Against all odds," in Abbas K. Kadhim, ed. Governance in the Middle East and North Africa: A Handbook (Routledge: 2013), pp. 357-81.

Tibawi, A.L. Arab Education in Mandatory Palestine: A Study of Three Decades of British Administration (Luzac & Co. Press Ltd.: 1956).

HBC-SU

Navigate the HBC Middle-East North African School Pages

[Algeria]

[Egypt]

[Iran]

[Iraq]

[Israel]

[Lebanon]

[Libya]

[Israel]

[Morocco]

[Saudi Arabia]

[Syria]

[Tunisia]

Related Style Pages in the Boys' Historical Web Site

[Long pants suits]

[Knicker suits]

[Short pants suits]

[Socks]

[Eton suits]

[Jacket and trousers]

[Blazer]

[School sandals]

Navigate the HBC School Section:

[Return to the Bain Palestinian British Mandate Education page]

[Return to the Main British Paestinian Mandate page]

[Return to the Main Palestine school page]

[Return to the Main Middle Eastern-Morth African school country page]

[Return to the Main school country page]

[About Us]

[Activities]

[Chronology]

[Clothing styles]

[Countries]

[Debate]

[Economics]

[Garment]

[Gender]

[Hair]

[History]

[Home trends]

[Literary characters]

[School types]

[Significance]

[Transport and travel

[Uniform regulations]

[Year level]

[Other topics]

[Images]

[Links]

[Registration]

[Tools]

[Return to the Historic Boys' School Home]

Created: 2:57 AM 11/7/2017

Last updated: 2:57 AM 11/7/2017