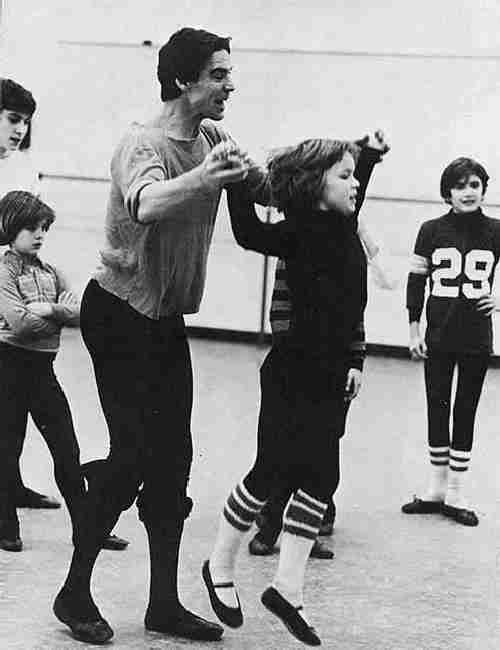

U.S. Boys' Ballet Costumes: Jacques D'Amboise

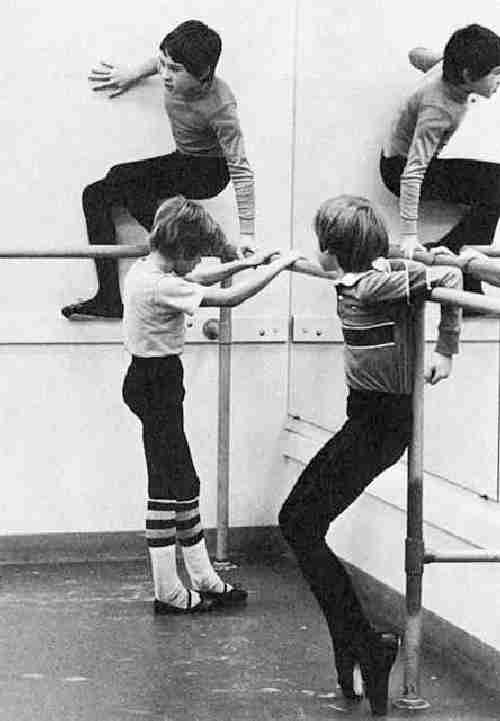

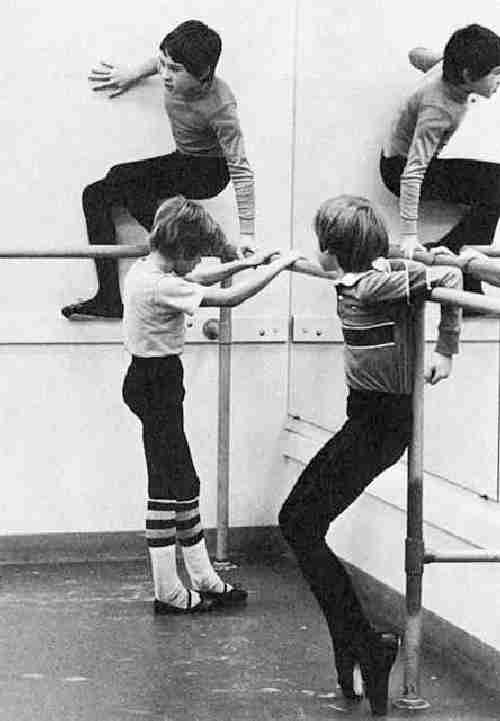

Figure 1.--The boys studying under Jacques D'Amboise wear an ecletic mixture od classical dance wear and other garments such as tube socks and knit shirts not normally associated with ballet dancing. D'Amboise is demanding, but he is flexible in dealing weith the younger children.

|

Sharing the exhilarating experience of dance has been Jacques d'Amboise's gift to children for the past two decades.Famed teacher and choreographer Jacques D'Amboise was born in 1934 at Dedham, Mass. He became a soloist with the New York City Ballet in 1953. He is best known for American-theme works, e.g., Filling Station, Western Symphony, films, e.g., Carousel (1956), and his own ballets, e.g., Irish Fantasy (1964). D'Amboise founded the National Dance Institute

in 1976 to bring the teaching of dance into the New York city public schools. He conducted classes in New York during the 1970s and 1980s amd continues tompromote dance education.

Youth

D'Amboise was born in 1934 to a French Canadian mother and Irish American father. He began dancing at age 7. He ran with the gangs in Washington Heights, bordering Harlem on the west side of Manhattan. Jacques credits his mother with sending him to ballet

classes at age 7 to keep him off the streets of the rough Washington Heights section of New York City. Even in childhood, he was a brilliant director. "I was always getting the kids on my block to play games, my games," he recalls. "If they didn't want to play I would change the story to give them the lead," he says. It was a move that foreshadowed his future success. He quit high school to perform at 15. He was invited by George Ballanchine to join the famous New York City Ballet. By the time he was 16, d'Amboise had performed at London's Convent Garden with the New York City Ballet, met the Queen and "when I came back to the block, I just didn't belong anymore."

Career

He was made a principal dancer at the age of 17 and appeared in his first movie the same year. He performed works by George Balanchine at City Ballet and appeared in movie classics such as Carousel and Seven Brides For Seven Brothers, as well as an Academy Award-winning documentary of his work.

Dance Education

D'Amboisee began a new career in 1976 when he founded the National Dance Institute (NDI) to teach public schoolchildren the joy of dance. He believes that dance and music are primary, like time and space. "Our heart beats in rhythm. We breath rhythmically. We're made of time; being expressed by movement. And by sound. The arts that humans have developed to

take this incredible fact of physics into expression are dance and music," d'Amboise says in a cadence that communicates pure joy.

"How did this happen?" D'Amboisee asks himself. "It was because of that early life of being actively engaged in the arts," he answered. Continuing this conversation with himself, he asked: "So how do I give back? Especially to young children, and especially boys

who are not in a position to have the economic means to have music lessons and dance lessons and poetry. How do I do that? "And I thought, ‘why don't you just go to local schools and start teaching little boys during school hours. Make sure they don't miss their play or lunch with their friends. Try to get it to be part of the curriculum. And then try to get them to experience what it is to do a public performance of high quality, where the music is the best and the scenery is the best, the theater is the best and your fellow performers

are all achievers."

And so, in between rehearsals at the New York City Ballet, d'Amboise went to his children's school and asked for "a place, an hour and if possible a piano," he recalled in his book Teaching the Magic of Dance. Six boys arrived as if a ball and bat would be the instruments of play. With those first rookies, the National Dance Institute began.

D'Amboise learned as the kids learned, discovering his own ability to work with children. "And I learned on the job. The best way to learn is to do," he says. The National Dance Institute grew, from 80 boys at the first performance to 400 boys and girls just a few years later.

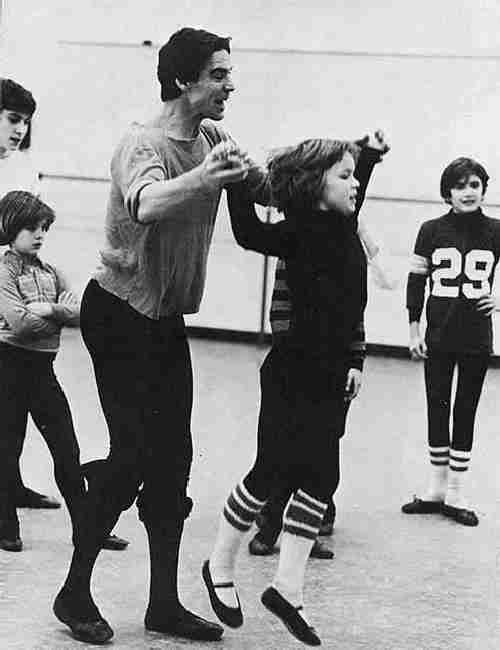

Figure 2.--D'Amboisee has a wonderful waybof working with boys. With this group hevinsists oin tights, but the boys can choose their shirts and socks.

|

D'Amboisee started working with boys primarily but eventually expanded the scope of his work. He estimates that over the last 23 years, NDI has taught more than half a million children. That is roughly 2,000 a year in

the New York area where NDI was founded, plus thousands more in NDI residencies around the country.

Although children train with top-notch NDI teachers and choreographers, the purpose is not to turn them into professional dancers, but to instill in them a dancer's sense of discipline and confidence. The teachers, who all have professional performing experience, spend approximately 70 hours with the children, over several weeks. In that time, what seems like barely controlled chaos becomes a polished performance through the alchemy of rehearsal.

D'Amboise credits his teaching skills to his own wonderful teachers. George Balanchine "was the best teacher I've ever met," he says. Balanchine asked a 15-year-old d'Amboise to choreograph a pas de deux as an exercise. Balanchine watched the piece without comment, then told d'Amboise to do a piece for eight people using circles. "He said it was very nice, but not very interesting--he got bored halfway through," d'Amboise recalls. Next assignment: Do it over, and make it exciting. In this indirect way, the great choreographer taught d'Amboise the ropes. According to d'Amboise, Balanchine thought teaching on a higher level is choreography, and choreography taken to its highest level becomes teaching on a higher level yet. "Teachers should be honored as much as doctors and lawyers," d'Amboise maintains. "They should be compensated accordingly and the highest paid should be elementary school teachers." The best teaching, according to d'Amboise, is always in the form of play: "Really good teachers are performing all the time. They use everything they can to engage you." d'Amboise advises teachers to appeal to children's sense of joy, curiosity and wonder rather than relying on fear tactics. "It's better to have them love what they learn and then challenge them to be excellent at it," he concludes.

D'Amboise believes in tapping into his dancers' creative ability, the way good directors work with actors. "The director has the entire piece to worry about, but the players have only their part, which they will have thought about far more carefully than the director," he says. "They'll bring so much richness, color and complexity to the role that your ideas will seem paltry by comparison." He also cautions teachers not to let dancers rely on tricks, such as constantly doing one step they're very good at: "It becomes an affectation. It raises cheers every time they do it, but it stops their growth."

A Class

The children on the eighth floor of Manhattan's LaGuardia High School for Performing Arts

probably didn't realize how privileged they were. They were too young to understand the concept of a living legend or to be impressed with National Medals of Arts, MacArthur Fellowships and honors from the Kennedy Center and American Academy of Arts and Letters.

But the two dozen kids--ages 3-10--who were doggedly running through a gangster-and-gun-moll routine were impressed enough with their director to do everything he

asked for right on cue. They took corrections, kept quiet offstage and, in general, behaved like pros.

That Jacques d'Amboise commands the respect of children may say more about his career than the honors, awards and accolades he has received over the years. Early in this painstaking process, d'Amboise repeatedly stops the performers to correct them. He insists on precision, and his breakdowns are a lesson in theater craft. "Watch me," he says, as he plays the bad guy in a scene where the gangsters pull off a bank heist. He rubs his hands together greedily as if to say, "It's mine, all mine!" while the children drag bags of money across the stage. As he proudly escorts two girls, he looks from one to the other and grins broadly to the audience.

He stops and turns to the kids. "See what I did? All the time I was talking to the audience. But you do it all without saying a word." d'Amboise has given the kids an object lesson in the communicative power of body language and gesture. Throughout the rehearsal, he never marks a step; he's always on, always demonstrates full out and is always clear. You always have to do your best, he notes, because children copy what they see.

At the end of the hour, the final run-through goes off without a hitch--a miracle considering how little time they've spent rehearsing. d'Amboise gathers his young charges about him and delivers a heartfelt speech, "Dancers, I think I've never seen anyone jump higher than you. You're the best. If I was ready to take a trip to outer space, I would want my crew to be you! We could go all around the stars." When the rehearsal ends, d'Amboise says, "Come on Sunday. It's going to be 70 percent better."

The Person

After you have seen d'Amboise in action, assuming one larger-than-life persona after another, it's startling to discover his off-stage personality: relaxed, playful and far more interested in conversing with you than talking about himself. He listens intently to what you say. Your opinions seem important to him. Dancers, especially children, would jump over the moon for anyone who cares this much. In short, he bowls you over with his charm; it is perhaps this quality that makes him such an effective teacher.

A Performance

A crowd of parents and friends flow into the lobby of the high school, buzzing with anticipation. The large auditorium quickly fills and as the lights dim, strains of Strayhorn and Duke Ellington can be heard in the air. One by one, the kids run on stage, do one star leap for the audience, then take their places. The emcee is played by silken-voiced Larry Marshall, veteran of both Broadway and La Scala. The show cleverly sneaks in a history lesson about jazz and Ellington's life, from the baseball diamond to the Cotton Club, with trips to the Far East and England for good measure. As Marshall speaks, the children react, assuming listening postures. One especially clever number, choreographed by Lori Klinger, features the future jazzman playing baseball as a child. When he got whacked on the head with a bat--a scene enacted with perfect timing on stage--his mother sent him to piano lessons, figuring it would be safer. A row of children become piano keys, shimmying when struck until all the ivories are swinging. Other highlights included an African dance number, a pas de deux choreographed by d'Amboise's son, Christopher, to a tune by Ellington and several large production numbers. NDI elieves dance should be accessible to all, and in this production children with visual and hearing impairments, as well as those in wheelchairs, danced with the rest. This was no ordinary dance recital; the dancing was crisp and clear, despite complex choreography. In fact, if you didn't notice the dancer's young faces, you'd think they had trained for years. The audience whooped with delight and spontaneously clapped in rhythm. D'Amboise was right about the rehearsal's effect, but the show improved by even more than his predicted 70 percent. It could have played on Broadway.

Later Life

Even in 1999 master dancer Jacques d'Amboise continued to be active training young dancers. At the National Endowment for the Humanities in 1999, d'Amboise gave a

preview of the activities he has planned for the 7-month Appalachian Trail hike he will begin in May to promote arts and humanities education. d'Amboise explained the purpose of

his journey and demonstrated the dance "jig" that will be the trek's theme in an appearance at an NEH forum in the Old Post Office Pavilion. Some 40 students attending from two Washington public schools--the Winston Educational Center and the Patterson Elementary School--learned the steps and experienced the rambunctious, inspirational teaching style of one of the nation's great dance instructors. "The humanities tell America's stories, and the voice of Jacques d'Amboise is one we can all learn from," said NEH Chairman William Ferris. "He is a national treasure, gifted not just as a dancer but as an interpreter who bridges the worlds of the arts and the humanities through word and deed. He is a great artist, a great humanist and a living legend." The dancer's distinguished 35-year career includes starring in George Balanchine's New York City Ballet, founding and directing the National Dance Institute in New York, and receiving a MacArthur "genius" award and the National Medal of the Arts.

Christopher Wagner

Navigate the Historic Boys' Clothing Web Site:

[Introduction]

[Activities]

[Bibliographies]

[Biographies]

[Chronologies]

[Contributions]

[Countries]

[Frequently Asked Questions]

[Style Index]

[Boys' Clothing Home]

Navigate the Historic Boys' Clothing Web chronological pages:

[The 1890s]

[The 1900s]

[The 1910s]

[The 1920s]

[The 1930s]

[The 1940s]

[The 1950s]

[The 1960s]

[The 1970s]

[The 1980s]

[The 1990s]

Navigate the Historic Boys' Clothing Web dance pages:

[Return to the Main U.S. ballet page]

[Return to the Main biography A-D page]

[Main dance page]

[Irish step]

[Kilts]

[Highland]

[Ballroom]

[Native American]

[Tap]

Created: November 20, 2000

Last updated: November 20, 2000