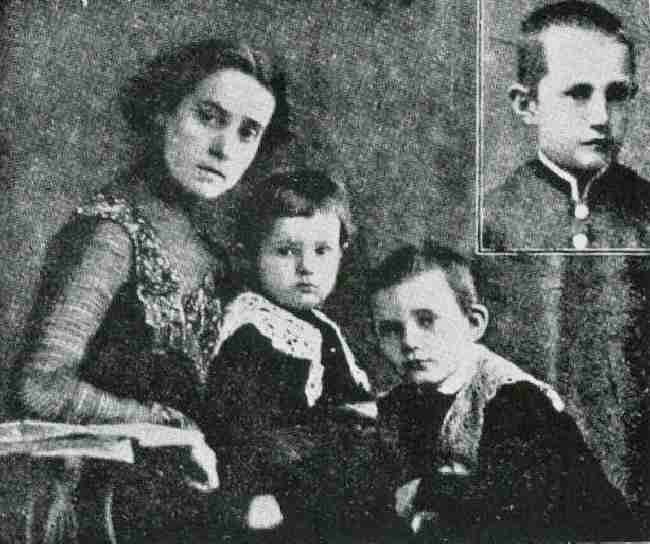

Figure 1.-- The Kerensky children are shown with their mother Olga Lvovna (nee Baranovskaya). The portrait was taken about 1912. The boys have pin on lace collars on their jackets. The insert is their father in his school uniform.

Kerensky, Alexander Feodorovich participated in the 1917 revolution aganst the Tsar.

Alexander Kerensky emerged as an important figure in the Russian government in

the transition between the reign of the Tsar Nicholas II and the Soviet

Communist dictatorship. He was a moderate socialist believing in a democratic government. He succeeded Prince Lvov's Provisional Government. Kerensky's Government was overthrown by Lenin's Bolsheviks (November 1917). Krensky eventually emigrated to the United States.

Alexander Kerensky's father was a school headmaster.

Alexander was born in Simbirsk, Russia, on April, 22, 1881.

Kerensky studied law at the University of St. Petersburg.

Many in Russia were radicalized by Tsarist policies in 1905. Kerensky joined the Socialist Revolutionary Party (SR) which at the time was banned as a subsersive group (1905). With his educational background he became editor of the radical newspaper, Burevestik. As a result, the Tsarist police arrested and exiled him. He returned to St. Petersburg and began working as a lawyer (1906). He often took political cases and developed a reputation for effectively defending Socialists and other radicals in court. Kerensky joined the moderate Russian Labour Party and in was elected to the Fourth State Duma (Russian parliamnent) (1912). Kerensky Socialis beliefs and persuasive speaking made him popular with workers in St. Petersburg. He gained some prominance when he exposed an important Bolshevik, Roman Malinovsky, as an undercover operative of the Okhrana (the Tsarist secret police).

Kerensky married Olga Lvovna (nee Baranovskaya). The image here shows the Kerensky boys (Glenb and Oleg) and their mother about 1912. Their mother refused to let me brought up in the Church. Oleg in particular proved to be an excellent student. The boys here wear lace collars. Another photograph a year later shows them wearing casual clothes. The family fled Russia with their father after the Bolsheviks seized power (November 1917). Both boys spent most of their adult live in Britain. Their father was disapointed that they did not persue politics.

Tsar Nicholas ordered the mobilization of the Russian Army when Austria-Hungary launched a punative invasion of Serbia for its role in the assauination of Arch Duke Franz Ferdinand. This forced Germany's hand. Germany feared the massive Russian Army once fully mobilized. As Germany could mobilize and move its Army much faster, Kasiser Wilhelm ordered full mobilization. The Germans struck first in the West, moving through Begium to knock Russia's ally France out of the War. Determined resistance by the small Belgian Army and the British Expedutionary Force (BEF) rushed to Belgium managed to slow the German advance. The German's were also distracted by Russian offensive in the East. The French managed to stop the Germans who were approaching Paris at the Marne. The War in the West then settled down into bloody trench warfare. As costly as the War was for the Allies in the West, in was many times more deadly on the Eastern Front. Russian troops were poorly led and supplied, unprepared for modern warfare. Many Russian soldiers did not even have rifles. German units were well supplied and backed up with deadly artillery and machine guns. Poison gas proved especially effective and Russia did not have gs masks to issue its troops. Russian losses were massive and as a result of the War food shortages were severe in Russian cities by 1916. Tsar Nicholas assumed personal command of the Army and as the War became increasingly unpopular, so did the Tsar.

Kerensky realising that the authority and reach of the Tsarist Government was failing, demanded the abdigation of Tsar Nicholas II (February 1917). He rejoined the Socialist Revolutionary Party. Tsar Nicholas finally abdicated (March 13). Prince George Lvov established a Provisional Government. He appointed Kerensky as Minister of Justice. He initiated a series of progressive reforms, abolishing capital punishment, recognizing basic civil liberties (especially freedom of the press), the ending ethnic and religious discrimination. He began planning for universal suffrage and democratic elections. The Provisional Government despite the deteriorating situation at the Front honored Russia's commitment to the Allies and did not take Russia out of the War. Nor did theGvernment address the problem of land reform.

Kerensky was appointed Minister of War (May 1917). He appointed General Alexei Brusilov as the new Commander in Chief of the hard-pressed Russian Army. He went to Front and delivered emotional speeches, pleading with the beleagered and poorly equipped Russian soldiers to continue fighting. Kerensky announced a new offensive (June 18). The Bolsheviks made peace an increasingly important part of their program and helped organize demonstrations crtiizing Kerensky. Brusilov's offensive focused on the Austrian Army in the Galician sector (July). He achieved some success, but the limited mobility of the Russian Army and lack of supplies made it difficult to persue the offensive vigorously. Reserves rapidly brought by the Germans from the Western Front stopped the Russian advance (July 16).

Pruince Lvov was determined to continue the War against Germany and did not persue any peace efforts. His popularity declined and was eventually forced to resign (July 8). Kerensky was the most popular man in the Government and thus ws chosen to replace Lvov. Kerensky had been leader of moderate socialists and champion of workers. Kerensky failed, however, to address the key concerns of Russians. He failed to take steps to address economic issues--especially land reform. Nor did he move to make peace. Despite the growing unpopularity of the War, Kerensky was also unwilling to withdraw Russia from the War. He even ordered a new summer offensive. The War by this time, however, was no longer sustainable. German superority in equipment had broken the morale of the Army. Whole regiments refused the orders of their officers to move to the front. Men deserted in increasing numbers. An estimated 2 million Russian soldiers had deserted (Fall 1917). This huge number of men, many with their weapons, left Russia in turmoil. Many had returned home and began seizin land from landords--for the most paret the Russian nobility. Some manor houses were destroyed and some of the landlords killed. Kerensky who made no move toward labnd reform threatned the use of force, but with the Army deteriorating had no way of stoping the violence in rural areas.

The influence of the Bolsheviks grew steadily in 1917. The Bolshevik ptomissed action on the key concerns of Russians, withdraw from the war and economic reforms, especially land reform. The Germans had arranged for Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin to travel from switzerland accross Germany to Russia as the Bolseviks were determined to end the War. The Bolsevik's appeal was "Peace and bread". Workers who had been denied unions by the Tsarist Governmebnt began forming Soviets and seizing control of factories. The Sovirts were able to obtain guns from deserting soldiers. Kerensky upon becoming premier attempted to suppress the Bolsheviks. Lenin was forced into hiding in. Other Bolshevik leaders, including Leon Trotsky , were arrested. The popularity of their program, however, made it impossible for Kerensky to supress them. The steadyily deteriorating the economic and military situation made Kerensky increasingly unpopular. The Bolsheviks used the Soviets (workers committees) to build their power. Soviets were also formed by soldiers and agricultural workers. It was the Soviets in Petrograd formed by workers and sailors that proved critical.

Kerensky replaced Brusilov when the July offensuve failed. He chose General Lavr Georgyevich Kornilov as the new Supreme Commander of the Army. The two clashed almost immediately over military strategy. Kornilov demanded that Kerensky restore the death penalty so he could have deserters shot. He also wanted to militarize the factories to ensure the production of arms. Unable to convince Kerensky, Kornilov moved to seize control of the Government. Kornoilov demanded that Kerensky's Cabinet resign and that military and civil authority be transferred to the Army which would allow him to establish a military dictatorship (September 7). Kerensky immediately dismissed Kornilov as Commander in Chief of the Army and recalled him to Petrograd. Kornilov ordered General Krymov to seize Petrograd. Kerensky who did not have control of Army units called on the Petrograd Soviets (workers organizations) the Red Guards to protect his Government. Both these organizations were controlled by the Bolsheviks. The Bolsheviks agreed, but party leader, Vladimir Lenin, made it clear to his followers that they would fighting to prevent Kornilov from seizing the Government, not to support Kerensky. Lenin's Bolsheviks ammassed a force of 25,000 men. They dug trenches and prepared to defend the city. Lenin sent delegations of soldiers who had joined the Bolsheviks to meet with the advancing troops who they comvinced to refuse to attack the city. Abanoned by this troops, General Krymov shot himself. Kornilov was arrested.

Kerensky now assumed personal command of the Russian Army. He maintained Russia's commitment to the Allies to keep Russia in the War. His popularity with workers was badly eroded by this commitment. He reorganized his Cabinet to gain more left-wing support (October 8). He brought more more Mensheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries into the Government. The situation in Petrograd, however, was untenable. The Army could not be relied on any longer. The only dependable force in the city was the Bolshevik controlled Soviets and the militia they had formed to protect the city. Kornilov's mutiny in effect destroyed the Kerensky Government. The Bolsheviks dominated the left because of Kerensky's unpopular policies. Kornilov's mutiny denighed the Government support from the right. Kerensky was thus left with few supporters. Armed groups were in the hand of the Bolsheciks on the left and the monarchists on the right. The narrow center had no armed group.

Kerensky lerned that the Bolsheviks were preparing to seize control of the Government (November 7). With few options, he left the city and attempted to rally support from the Army at the Front. The Red Guards proceeded to storm the Winter Palace and arrest members of Kerensky's cabinet. Kerensky with loyal troops from the Northern Front moved toward Petrograd, but were defeated by the Bolshevik at Pulkova with many of the Army troops refusing to fight.

Kerensky fleed to Finland, at the time part of Russia. He remained underground there. As the Finns were moving toward independence the Bolsheviks could not arrest him. He managed to reach London (May 1918). After the War he lived in France where he spoke and wrote against the Bolshevik regime in Russia. He published the Russian-language newspaperDni which was , that published in Paris and Berlin. Kerensky was also critical of the NAZIs, especially after the signing of the NAZI-Soviet Non-Aggression Pavt (August 1939).

After the NAZIs invaded Poland and World War II began, Kerensky emigrated to America (1940). He continued to speak out against Bolshevism in Russia. He worked with the Hoover Institution in California and wrote his autobiography. He died from cancer in New York (1970).

Kerensky. Alexander. The Catastrophe (1927).

Kerensky. Alexander. The Kerensky Memoirs: Russia and History's Turning Point (1967).

Kerensky. Alexander. The Prelude to Bolshevism (1919).

Abraham, Richard. Alexander Kerensky: The First Love of the Revolution (New York: Columbia University Press, 1987).

Navigate the Boys' Historical Clothing Biography pages:

[Return to Main bio page]

[Return to Main photographer page]

[Biographies A-F]

[Biographies G-L]

[Biographies M-R]

[Biographies S-Z]

Navigate the Boys' Historical Clothing Web Site:

[Introduction]

[Activities]

[Biographies]

[Chronology]

[Clothing styles]

[Countries]

[Bibliographies]

[Contributions]

[FAQs]

[Glossary]

[Satellite sites]

[Tools]

[Boys' Clothing Home]