Nicaraguan History: American Intervention (1909-33)

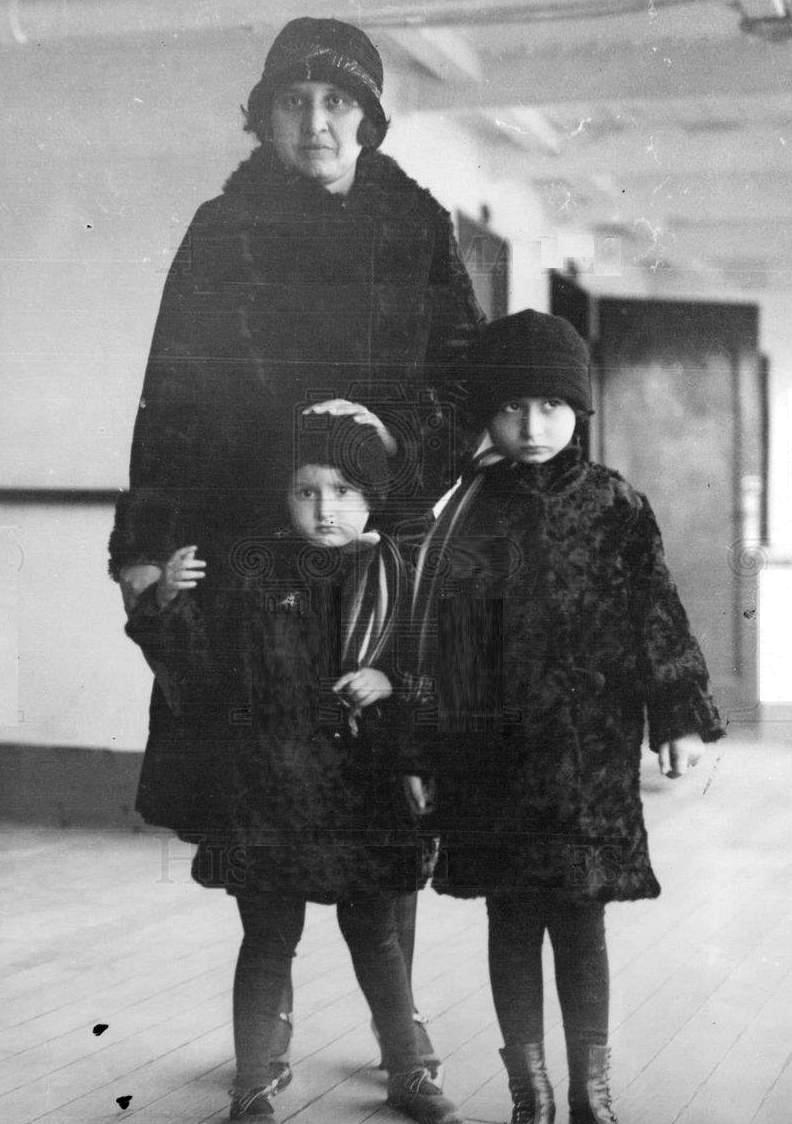

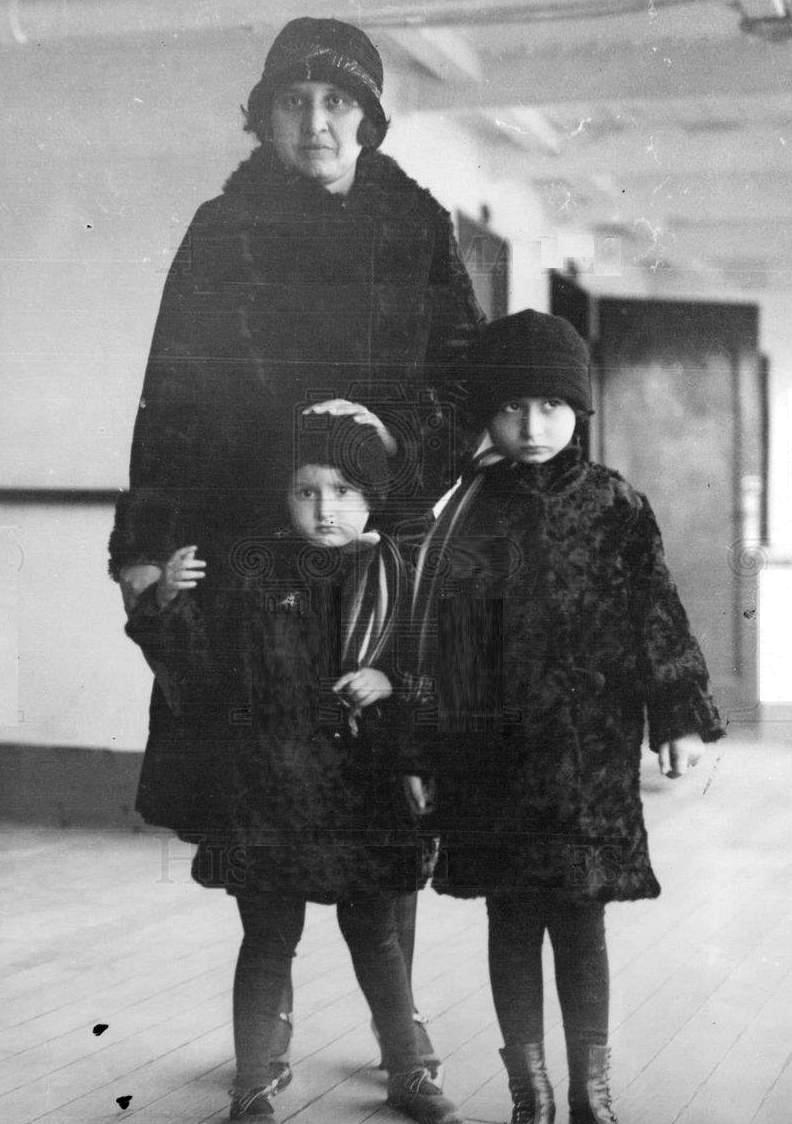

Figure 1.-- President Coolidge withdrew the U.S. Marines (1925), but irdered them back after violence spiraled again over the results of the 1924 election (1926). Here are two refugees from the fighting who reached Los Angeles. One gets the impression that Señora Nevas thought she was headed for laska. The caption read, "They saw the burning of Chenandaga in Nicaragua: Mrs. Octvio Nevas with her two children, who fled from Nicaragua and brought with them horrible tles of slaughter and desolation when the city of Chenandaga, was bombed from the air, in an attemot to rout the liberals [rebels]." The photograph is dated March 18, 1927. Chinanddega (modern spelling) is located in an agricultural neighborhood, but close to the importnt port of Corinto. We are unsure how to interpret this. We know that Rebel forcs occupied Chinandega (February 1927). At the time U.S, Marines landed at the nearby port of Corinto. As far as we know neither the Marines or Navy in Nicaragua had bombers, but one historian confirms that the rebel-held city was bombed. [Staten, p. 45.] Nor did the Government.. The Marines and Government forces would have had artillery. Naval shelling is also a possibility.

|

|

Nicaraagua became on of countries involved in what some historians label, the Banana Wars. Relations with the United States deteriorated, especially after President Zelaya approached the Europeans about a competing canal. The Panama Canal was nearing completion. And the security of the Canal had become a central factor in American strategic thinking. As was the case with European countries, debt repayment was also a factor in the Banana Wars, including Nicaragua. American diplomats becan encouraging Zelaya’s Conservative opposition to challenge the long-time dictator. A rebellion ensued. Governent forces executed two U.S. citizens participating in the revolt, the United States Navy landed a small contingnt of marines in Bluefields on the Caribbean coast. This essentially prevented a Liberal victory. President Zelaya resigned (1909). Amrican authorities, however refused to recognize his replacement, José Madriz (1909–10). The rebellion moephed into a civil war. This led to Conservative, Adolfo Díaz becoming president (1911–17). It was to support Díaz that President Taft ordered in the Marines in force (1912). A 100-man guard at the U.S. Embassy in Managua came to symbolizeAmerican support for for Conservative presidents Emiliano Chamorro Vargas (1917–21) and his uncle Diego Manuel Chamorro (1921–23). The Bryan-Chamorro Treaty (1914) gave the United States what it primarily wanted--exclusive canal privileges in Nicaragua and the right to establish possible naval bases to protect the Panama Canal. The Unites States now that the Panama Canal was completed had no intention of building a second cnal in Nicaragua, but was intent on making sure that no one else did either. The Marines also guaranted debt repayment. After World War I and the decline of preceived security threats to the Panana Canal, President Coolidge withdrew the Marines (1925). He then ordered them in again to restore order after the disputed 1924 elections (1926). The Marines remained for nearly a decade. It is at this time that a teenager would begin a resistance movement -- César Augusto Sandino. He became a guerilla leader and organized small-scale resisrance in rural areas (1927). This would cintinue until President Franklin Roosevelt in the first year of his presidency launched the Good Neighbor Policy finally and finally withdrew the Marines (1933).

Nicaraguan Politics

As in many Latin American ciyntries, politics was dominated by differences between liberals and conservatives. In Nicaragua there was also a regional element because the two parties dominated the country's two major cities. Liberals dominated the city of León, and the Conservatives, dominating Granada. This led to essentially a civil war in the 19th century. Conservative Granada had long played rival to the colonial capital, Liberal León. A compromise, designating the small fishing village of Managua as a new national capital (1852). The León-Grenada split dominated 19th century politics, at times leading to violence. This was finally nded by Presidebt Zelaya's Liberal dictatorship. Conservative resentmnt seathed.

Panama Canal

The Istmus of Panama became an important crossing point from the Caribbeb and Pacific early in the Spanish colonial period. It was, however, a land crossing and remained that way for four centuries. It was the route Pizzaro ook to conquer the Inca Empire and the route that Bolivin silver took back to Spain. It was a short route, but not an easy one as it led through nearly inpenetrable jungle. And it exposed travlers o incurable diseases like malaria and yellow feaver. It was the fastest route for Americans trying to get to California when gold was discovered in California (1848). French diplomat and entrepreneur Vicomte Ferdinand Marie de Lesseps (1805-94) who had played a najor role in building the Suez Canal got involved in a French project to build a Panamanian canal acros the Istmus of Panama. The project failed resulting un a financial scandal. Yellow fever was one of the mjor reasons the French project failed. Panama at the time was part of Colombia. American President Theodore Roosevelt decided that a canal could and should be built. Different routes were considered, including a Nicarguan route. Nicaraguan President Zelaya rejected the idea. Unlike the French, the Unitd States had the financial and industrial strength to take on this enormous project, especially when the U.S. Governmnt became involvd. President Roosevelt convinced the U.S. Congress to take on the abandoned French works (1902). An American proposal for canal rights over the Isthmus was rejected by the Colombian Senate. Panamaians seized the opportunity, proclaimed their independence, and received U.S. support (1903). The new government signed a treaty with the United States. Panama granted the United States canal rights in perpetuity, The United States proceeeded to build the canal--one of the great engeneering achievements of the age. In addition to the engineering, work donne by Walter Reed in Cuba was applied in the Camal Project and fior the first time gelped to cintro yellow fever and malaria in the region. Roosevelt saw it as his most important achievement. Panama received $10 million and an annual payment of $0.25 million. The canal was formally opened with the passage of the cargo ship SS Ancon (August 15, 1914). This was 2 weeks after World War I broke out in Europe. Even before the Cnal was pened, it necame a major facor in American strategic thinking. The United States required a two ocean navy. The Panama Canal provided a way to rapidly move ships from one ocean to another to deal with emergncies. As a result, th U.S. Navy designed ships only wide enough to pass through the Canal.

American-Caribbean Wars / Banana Wars (1912-33)

The American-Caribbean Wars are referred to by many historians as the Banana Wars because of the economic

aspects of the American actions in the Caribbean. And bananas were an important part of the story, but not the only commodity. Coffee and sugar was also important. Bananas were a new commodity. The United States removed import duties on bananas (mid-1880s). As a result banana cultivation expanded from Cuba and other Caribbean islands into Central America, including Mexico, Honduras, Costa Rica, Panama, and on to South American countries like Colombia abd Ecuador. As a result, the bananaas aopular, well known friot throughout the United States (1890s). The Caribbean (including Central America ) was the major source of bananas and American investors (especually the United Fruit Company) became heavily involved. There were other issues involved besides American investment in agriculture, the two most important were debt repayment and the security of the new Panana Canal. Debt repayment was a recuring problem throughout Latin America. Latin American politics were tumultious involving short-term regimes replaced by wars, coups, and sham elections. Corupt dictators would vorrow money from European and Amercan banks and then leave it to the next dictator to pay the loans off. Usually there was a reluctance to do so. The bankers pressed their givernmnts for assiatance. In the Caribbean the debt repaymebt issue for Aneruca was intensified by security issus rising from the Panana Canal. Protection of the Canal became a primary American American security interest and a major concen for the U.S. Navy. The American-Caribbean Wars involved a series of occupations, police actions, and interventions involving the United States in the Caribbean including Central America. Amerivan involvemnt in the region began with the Spanish-American War (1898-99). The resulting Treaty of Paris with Spain gave the United States control over Puerto Rico and Cuba. The United States would then intervene in Panama (at the time part of Colombia) to build the Pananma Canal (1904). Subsequent intervenions occurred in Honduras (1903), Nicaragua (1912), the Dominican Republic (1914), Haiti (1915), and Mexico (1917). Popular American author O. Henry coined the term 'Banana republic' to describe Honduras where the United Fruit Comoany was especially involved and bananas were especially important (1904). The American Caribbean Wars finally ended with withdraals during the Hoover Administration and President Franklin Roosevelt's Good Neighbor Policy (1933).

Anti-Zelaya Rebellion (1909)

Nicaraagua became one of countries involved in what some historians label, the Banana Wars. Relations with the United States deteriorated, especially after President Zelaya approached the Europeans about a competing canal. The Panama Canal was nearing completion. And the security of the Canal had become a central factor in American strategic thinking. As was the case with European countries, debt repayment was also a factor in the Banana Wars, including Nicaragua. American diplomats began encouraging Zelaya’s Conservative opposition to challenge the long-time dictator. A rebellion ensued that quickly morphed into a civil war (October 1909).

Anti-Zelaya liberals joined forces with the Conservatives headed by Juan Estrada in an effort to oust long-time dictator José Santos Zelzya. Zelaya Governent forces executed captured rebels, including two American mercenaries participating in the revolt. The United States broke diplomatic reltions. The U.S. Navy landed a contingnt of 400 Marines in Bluefields on the Caribbean coast. This essentially prevented a quick Zelaya victory. President Zelaya seeing his grip on power weakned by bith Libseal defections and American opposition, resigned and fled to Spain (December 1909). American authorities, however refused to recognize his replacement, Zelaya's foreign minister, José Madriz (1909–10). Madriz, was appointed president by the Liberal-dominted Nicaraguan Congress. He was a Liberal from León, but was unable to restore order under continuing pressure from conservatives and the United States forces, and he resigned (August 1910).

Conservative Control

José Dolores Estrada Morales, in the wake of the turmoil following José Santos Zelaya's fall, briefly served as acting President of Nicaragua for a week before handing power to his brother, Juan José Estrada (August 1910). Estrada was the governor of Nicaragua's easternmost (Caribbean) department. The United States was willing to support him as long as a Constituent Assembly was elected to draft a new constitution followed by elections. A coalition Conservative-Liberal regime, headed by Estrada, was recognized by the United States (January 1911). Liberal-Conservative cooperation did not last long. Minister of war General Luis Mena forced Estrada to resign. Estrada's vice president, Conservative Adolfo Díaz temporarily assumed the presidency. Mena persuaded wjo controoled the military convincd th Constituent Assembly to appoint him to suceed Díaz when Díaz's term expired in 1913. The United States refused to recognize the Constituent Assembly's appoitment of Mena. Mena rebelled against the Díaz government. And a force led by Liberal Benjamín Zelaydón quickly came to Mena's assistance. Díaz requested American assistance.

First American Intervention (1912-25)

It was to support Díaz that President Taft ordered in the Maines in force. The United States landed a force of 2,700 Marines at the Caribbean ports of Corinto and Bluefields (August 1912). Mena fled and Zelaydón was killed in the resulting fighting. The United States did notvattempt to size Nicaragua or administer it, kept a small force of Marines in Nicaragua almost continually from 1912 until 1933. The unintial intervention force was reduced to 100 men (1913). The Marines who became known as the Legation Guard were basically a statement that the United States was willing to use force and to keep Conservative governments in power. There was no substabtial resistabce. The United States supervised national elections (1913). The Liberals boycotted the election, although as far as we know it was an free election. Adolfo Díaz was reelected to a full term. Nicaragua and the United States signed but never ratified the Castill-Knox Treaty (1914). This would have given the United States the right to intervene in Nicaragua to protect United States interest--similar to the Platt Amendment. A revised text, the Chamorro-Bryan Treaty omitting the intervention clause, was finally ratified by the United States Senate (1916). The Treaty gave the United States what it primarily wanted--exclusive interoceanic canal privileges in Nicaragua and the right to establish possible naval bases to protect the Panama Canal. The Unites States now that the Panama Canal was completed had no intention of building a second canal in Nicaragua, but was intent on making sure that no one else did either. The Marines also guaranted debt repayment. This led to Conservative, Adolfo Díaz becoming president (1911–17). With American support, he was followed by presidents Emiliano Chamorro Vargas (1917–21) and his uncle Diego Manuel Chamorro (1921–23).

American support enabled the Conservatives to hold on to power until 1925. Liberals boycotted the 1916 election allowing Conservative Emiliano Chamorro to be elected without opposition. The liberals did participate in the 1920 elections, but American backing and election fraud resulted in the election of Emiliano Chamorro's uncle, Diego Manuel Chamorro. After World War I and the decline of preceived security threats to the Panana Canal, President Coolidge withdrew the Marines (1925).

Election of 1924

Nicaragua held a free, democratic election (1924). Moderate Conservative, Carlos Solórzano, was elected president. And as a way of healing the butter partisan divide, Liberal Juan Bautista Sacasa waselected his vice president. After taking office (January 1, 1925), Solórzano asked the United States to delay the withdrawal of the Marines. Nicaraguan and the United States officials agreed that the Marines would remain while U.S. military instructors helped train an effective national military force. The Solórzano's government contracted U.S. Army Major Calvin B. Carter to establish and train a National Guard (June 1925). The U.S. Marines departed Nicaragua (August 1925). At this point the situation in Nicaragua began to fall apart. President Solórzano purged the Liberals from his susposedly coalition government. He was forced out of power by Conservatives group who proclaimed General Emiliano Chamorro president (January 1926). Chamorro was a previous president. All of this led to raising disorder and political violence.

Second American Intervention (1926-33)

President Coolidge soom after withdrawing the Marines, ordered them in again to restore order after the disorder arising from the 1924 elections (1926). With the defeat of Germany in World War I, there were no longer serious security concerns. Other issues, however, had arrisen. There was the concern over another round of Conservative-Liberal violence. But perhaps the deciding factor was incrasing concern with radical left-wing political movements. There was the concern that disorder in Nicaragua might lead to a leftist seizure of power as ocuured with the Mexican Revolution (1910-20). And the Russian Revolution (1917). America had its own Red Scare after World War I. Socialism and Communism was having increasing appeal in Latin America amomgbintelectuals and labor unions. The abject failure of both wherever tried was not yet known, although even today with failure well known, here is still widespread support for thee ideas in Latin America. (The major opposition parties in Venezuela, for example, are socialist parties.) The Marines landed (May 1926). President Cooldidge justified the intervention to Americans as necessary to protect United States citizens and property. The U.S. Embassy in Nicaragua mediated a peace agreement between the Liberals and Conservatives (October 1926). Chamorro under pressure resigned. The Nicaraguan Congress elected Adolfo Díaz as president. Díaz had also previously served as president (1911-16). Violence occurred when former Liberal Vice President Sacasa returned from exile and claimed to be the rightful president. Sacasa was unaccptable to the United States because of Mexican ties, which at the time was seen as virtual Communism. [Staten, p. 45.] President Cooldidge dispacted future Sectrtary of State Henry L. Stimson (April 1927) to mediate the an end to the violence. Stimson began conversations with President Díaz as well as with individuals from all the important factions. Stimson met with General José María Moncada, the leader of the Liberal rebels. He made it clear that the United States would not allow Díazto be defeated militarily. [Staten, p. 45.] Moncaa agreed to a political settlement ending the fighting. Moncada agreed to a plan in which both sides would disarm (May 1927). A nonpartisan security force was to be established under American. This peace plan known as the Pact of Espino Negro. The Pact further provided that President Díaz would finish his term and the U.S. Marines would remain in Nicaragua to maintain order and supervise the 1928 elections. Sacasa refused to sign the agreement and left the country. The United States forces took over security functions. As part of tht effort they began to strengthen the National Guard. American intervention in Nicaragua would cintinue until President Franklin Roosevelt in the first year of his presidency launched the Good Neighbor Policy finally and finally withdrew the Marines (1933).

César Augusto Sandino

The U.S. Marines during the second American intervention remained for nearly a decade. It is at this time that a teenager would begin a resistance movement -- César Augusto Sandino. He became a guerilla leader and organized small-scale resisrance in rural areas (1927). Sandino also refused to sign the Pact of Espino Negro. He was the illegitimate son of a wealthy landowner and a mestizo servant. He ran away from his father's home as a teen ager and traveled widely in the region (Honduras, Guatemala, and Mexico). He lived 3 years in Tampico, Mexico. This was at a time just after the Mexican Revolution in which Mestizos played an important role. It was here that he became embued with a strong sense of Nicaraguan nationalism and pride in his own mestizo heritage. At the time Spanish (European) Latin Americans were seen as the most prestigious groups while Mesticos were of a lower social order. Africans and Indians made up the lower orders of society. Sandino returned to Nicaragua at the encouragement of his father (1926). He returned to Nueva Segovia Separtment and worked at an American-owned gold mine. Sandino lectured the lrgely uneducated mine workers about social inequalities and the need for political change. He soon acquired some devoted followers and began organizing a small military force recruiting peasants and workers. This was no middle class effort, but a genuine proletarian force. He supported the Liberals fighting the Chamorro's Conservative regime.

Yhis was, however, no combined effort. Liberal Gen Moncada distrusted him as a dangerous radical. Sandino staged hit-and-run operations against Conservative forces entirely independently of Moncada's Liberal army. After the United States mediated an end to the civil war and Moncada agrred, Sandino called him a traitor. He denounced he American intervention. He reorganized his forces as the Army for the Defense of Nicaraguan Sovereignty (Ejército Defensor de la Soberanía de Nicaragua-EDSN). Sandino then continued his guerrilla campaign against both the government and American forces. Sandino's initial gol was tp restore constitutional government under Vice President Sacasa. Thus chnged with the Pact of Espino Negro. His goal became the defense of Nicaraguan sovereignty against American intervention. He operated almost exclusively in rural areas where he found support anong the campesinos. He claimed to have some 3,000 troops, but a much smaller force is likely. Sandino's guerrillas rarely took on the U.S. Marines who at any rate were mostly osted in the cities. Sandinos operations did cayse serious physical damage along the Caribbean coast and in mining regions. American forces were unsure how to respond. In the end they declined to wage a major campaign aginst Sandino and his guerrilla force. Instead the Americans concentrated on developing the nonpartisan Nicaraguan National Guard to deal with domestic violence. The National Guard as America prepared to depart would become the most important force in Nicaragua.

The Battle of El Sauce (Punta de Rieles) was the last major battle of the Sandino Rebellion (December 1932). It was a victory for a National Guard force which included a few Marines and pergaps most importabtly the Browning Automatic Rifle (December 1932).

Elections and Withdrawl (1928-33)

The Espino Negro pece settlement made possiblde a peaceful election (1928). It would be a free an open election, arguably the most dmocratic election ever held in Nicaragua. Liberal military commnder Moncada won the presidential elections. The United States was soon focused on the Depression. Few Americans understood or cared about the Caribbean or Central America. Although President Roosevlt enunciated the American Good Nr=eughbor Policy, its beginnings lay with the Hoover Administration. President Hoover began unwinding the various American interventions in the Caribbean. The United States turned over command of the National Guard to the Nicaraguan Government. The Hoover Administration started the American pullout. Only 745 men remained (Feruary 1932). The Liberals nominated former Vice President Juan Bautista Sacasa for their 1932 candidate. The Conservatives turnd again to Adolfo Díaz. Sacasa won the elections and was finally installed as president (January 1933). The last United States Marines were withdrawn the day after the inaguration of President Sacasa (January 1933). President Sacasa, at the suggestion of General Moncada, appointed Anastasio 'Tacho' Somoza García as chief director of the National Guard. Somoza García was a close persinl friend of Moncada and nephew of President Sacasa. He had supported the 1926 liberal revolt6. Somoza García also enjoyed support from the United States government because of his participation at the 1927 peace conference as one of Stimson's interpreters. He had attended a school in Philadelphia and been trained by United States Marines. With his English fluency, he had developed associations with Amrican military officers, investors, and government officials. .

American Good Neighbor Policy

Latin American countries at the Sixth Pan-American Conference in Havana (1928) criticized the United states for its armed interventions. Presidents Roosevelt, Taft, Wilson, Harding and Cooldildge had all been involved in these interventions. At the time dring the Coolidge Administration, U.S. Marines were still in both Haiti and Nicaragua. This reflected a nadir in American relations with the United States. Newly elected President Herbert Hoover agreed that American policy needed to change. He coined the phrase, 'Good Neighbors'. Hoover went on a goodwill trip to Latin America after his 1928 election. He gave a speech in Honduras in which he declared, We have a desire to maintain not only the cordial relations of governments with each other, but also the relations of good neighbors." And during his presidency he followed up on ths by adopting policies to improve relations. The Clark Memorandum essentially retracted President Roosevelt's Corollary to the 1823 Monroe Doctrine (1930). The Roosevelt Cororollary asserted that only the United States could collect debts owed to foreigners by countries in the Western Hemisphere. The Clark Memorandum did not repudiate the American right to intervee. Hoover also withdrew the U.S, Marines from Nicaragua and planned their removal from Haiti which had been the greatest irritant in Hemispheric relations. Unfortunately the Wall Street Crash and ensuing Depression caused not only economic hardship in America, but other countries as well, including Latin America. The Smoot-Hawley Tariff was especially damaging (1930). President-elect Roosevelt at the behest of adviswers like Adolf Berle also concluded that a reset was needed in American relations with Latin America. The new President in inaugural address even raised the issue. He commited to improving regionaal relations. "In the field of world policy, I dedicate this nation to the policy of the good neighbor — the neighbor who resolutely respects himself and, because he does so, respects the rights of others." President Roosevelt continued Hoover's iniative. Secretary of State Cordell Hull was given the task of improving relatios with Latin America. Secretary Hull at the Seventh Montevideo-Pan-American Conference in Uruguay committed the United Sttes to a policy of non-intervention (1933). A major step was lowering tariffs. The impact of Smoot-Hawley Tariff had hurt Latin American economies, many of which were based on eporting raw materials. Cuba which was dependent on sugar had been especially hard hit. The United states also renegotiated the Panama Canal Treaty (1936). And the United States restrained from intervening when Mexico expropriated foreign mostly American oil companies (1938). The American Good Neighbor meant that well before the World war II crisis had begun, the United States had done a good deal achieve non-hostile neighbors to the south. This greatly eased the task of securing Latin American cooperation in the War effort, chiefly by maintaining the unterupted flow of petroleum and other crtical raw materials.

Sources

Staten, Clifford L. The History of Nicaragua (ABC-CLIO: 2010), 175p.

CIH

Navigate the Children in History Web Site:

[Return to the Main Nicaraguan history page]

[Return to the Main Central American history page]

[Return to the Main Latin American history page]

[Return to the Main Latin American page]

[Return to the Main Nicaraguan page]

[Introduction]

[Biographies]

[Chronology]

[Climatology]

[Clothing]

[Disease and Health]

[Economics]

[Geography]

[History]

[Human Nature]

[Law]

[Nationalism]

[Presidents]

[Religion]

[Royalty]

[Science]

[Social Class]

[Royalty]

[Bibliographies]

[Contributions]

[FAQs]

[Glossaries]

[Images]

[Links]

[Registration]

[Tools]

[Boys' Clothing Home]

Created: 2:54 PM 8/1/2017

Last updated: 2:54 PM 8/1/2017