Ernest Heminway, the noted American novelist, was born in 1898 and raised in Oak Park, Ill. His tough guy, hard boilled style had a profound influence on other American authors. In contrast to this image,

he was rather a coddled child. His mother doted on him and outfitted Ernest and his older sister in identical dresses when he was a small boy and insisted he pursue cultural activities such as music lessons and singing. His father, however, encouraged him to pursue outdoor activities such as hunting and fushing. Ernest reveled in the outdoors and secretly turned the music room into a boxing ring, a step even his father would not have approved.

Ernest's parents were two very different people. There were, however, some similarites. Both grew up in Chicago in the Victorian tradition. Both saw themselves as members of the upperclass. They proded themselves

in their relogious faith, support of missionary work, and appreciation of culture and the fine arts.

I have few details on the boyhood of Ernest's father. He certainly grew up in a moral rural setting than Ernest. I do not know how he was dressed as a boy. Ernest's father's pashion was for medicine and he became a doctor. He did his internship in Scotland. He was a little older than his wife. He wanted to be a medical missionary, but his wife would have none of that. So the Hemingways settled down with a successful medical practice in the comfortable Chicago suburb of Oak Park, Illinois. Dr. Hemmingway also loved the outdoors and nature, but not competive sports. He suceeded in passing on his love of nature to his son. As a youth he even spent a summer with the Souix Indians, a rather uncommon experience. The experience furthered his love of nature and admiration for the Indians. When he became a doctor he did charity work for them. As soon as Ernest was old enough, his father began taking him hunting and fishing, before he could say "pish"--which became a comstantly

retold family story. When Ernest asked to be read to, his father pulled out nature books and 3-year old Erbest became an expert on the birds of North America.

His mother's passion was for music. She studied piano and music. Her parents would not allow her to continue her studies in Europe, it was considered too bold. She did study extensively in America, including Manhatten--rather adventurous for the day. She latter recalled how, champeroned by her younger brother Leicester, she rode a high-wheeler bicycle on outings--no common for a proper young Victorian. Mrs. Hemingway was not exactly the protypical mother. Her son Leicester wrrites that her motherly talents were limited to breasted feeding and

lulibies, "She abhored didies, deficient manners, stomahe upsets, house cleaning, and cooking. As a result, the Hemmingways had a steady stream of nurses and mother's helpers.

The first baby, Marcelline, arrived in 1898 and Ernest soon after in 1899. Ursula was born in 1902 and Madeline (known as Sunny) arrived in 1904. Sunny was beyond a doubt Ernest's favorite. She was soon

tagging salong when Ernest went fishing and hunting and the two even

developed their own private language. Leicester arrived rather late in 1915.

|

Mother complained that Ernest cried a lot as a baby. Mother noted in the family records that he was breast fed for a year, gained weight rapidly, teethed early, and was walking at a year. He reportedly indulged in a jibbering lingo of his own. He tried at an early age to keep up with his big sister. His mother wrote, "Marcie was such a darling that Earnest was almost 2 before he managed to claim his full share of attention. By then he was such a strongly independent child." One way little Ernest used to get attention was using what the family

referred to as "naughty words". Mother's remedy was soap. "Go was your mouth out with soap," was a common refrain in the Hemmingway household. The soap apparently made a strong impression. He was later to write an

essay for Esquire, "In defense of dirty words." As she had with Marcelline, Grace began a scrapbook on her

second child's development from the day he was born. July 21, 1899, was a warm day, she noted. Baby Ernest weighed

9 1/2 pounds, was plump and perfect in form and had a marvelously deep-toned voice, a mahogany-colored complexion, "Grandpa Ernest Halls. nose and mouth," hands and nails Just like Grandpa Ernest's, dark blue eyes and thick black hair-which soon turned blond. She carefully choronicled Ernest's development for years.

Grace dressed newborn Ernest primarily in a baby dress that she had worn as a baby. After a couple months he frequently appeared in a white lacey dress with pink bodice [and] light blue shoes ... that Marcelline wore in her year old photograph. Grace dressed him up for a a formal portrait at a photographic studio,

in the same dress she dressed his sister Marcelline in at the same age for her formal photograph. Soon Grace began buying two of everything, often in different sizes when she purchased children's clothes.

We have a good deal of information about the way Grace dressed Ernest as a young boy. It is a topic many biographers have dealt with.

Grace's first identical outfits for Marcelline and Ernest's included crocheted bonnets, three-quarter-length coats, and ruffled dimity skirts that fell just to their ankles. Afterwards their outfits included garments like pink gingham frocks with white Battenberg lace hoods. Other outfits included fluffy lace-tucked dresses, black patent-leather Mary Janes, high stockings, and large hats with flowers on them. This is a good example of how Ernest's outfits did not have boyish touches. Often a hat with flowers is a good indicator that the child in question is a girl. Grace's attitude is illustrated by a photograph of Ernest taken behind Grandfather Hall's house in 1901. It is clearly Ernest wearing a picture hat and ankle-length frock, but but Grace has written summer girl. She notes for a series of group photos dated October 1902, these groups [were] taken when Ursula [the Hemingways' third child] was 6 months old; Ernest Miller 31/2 yrs; Marcelline, 4 3/4 years. The two older children (Marcelline and Ernest) "were then always dressed alike, like two little girls". Photographs of Ernest exist at various ages (2, 3, and probably about 6 years). He seems to have gone from dresses to regular boys clothes without the transition of kilts or other fancy suits which was a common convention at the time. He and his sister were dresses alike as children because his mother wanted them to appear as twins, even though there was over a year difference in their ages. Usually this meant dresses, but in the summer while vacationing at the lake, she still dressed them both alike, but as little boys. Mrs. Hemingway had wanted a daughter. When her first child Marcellin arrived, she was thrilled when it was a girl. She saw the child as a little copy of herself. She must have conceived of fulfilling her own twarted musical ambitions that her own mother had had for her. Ernest arrived 18 months later in 1899. Grace named him Ernest Miller. Ernest's name sake was Grace's beloved father. Miller was for her father's brother Miller Hall. She wasn't quite sure what to do with a boy. Despite the masculine names, she followed a popular fashion of the day and outfitted him in dresses, often identical to those worn by his older sister. But it was not always dressing Ernest in identical dresses worn by his older sister. Grace seemed to be especially smitten with the twin look. Sometimes she would dress Marcellin in little boys clothes, of course identical to the clothes worn by Ernest. At home dresses were most common, but for outdoor activities like hiking and fishing at their country cottage, the boys clothes were more common. I am not sure how common this was. I have the idea that once boys received their first kneepants, they did not thersafter wear dressses. Although it might have been a few weeks before a complete wardrobe was purchased.

|

Kenneth S. Lynn's book on Hemingway makes quite a lot this and tries to show that dressing little boys like their sisters in the 1890's was unusual. He admits that this was frequently the case for boys under 2, but for boys over 2, only to about 1 in a 100. I do not have any information on the frequency the various

clothing styles were worn? The length of time the various styles were worn depended greatly on the economic situation, as well as the desires of the boy's mother. I believe that he is underestimating the number

of boys that were still outfitted in dresses at the turn of the century. It was becoming less common, but was not nearaly as unsual as the author suggests. It does appear that by 2 or 3 years, some boys were being dressed in knee pants. However, given the number of dresses for boys shown in clothing catalogs up to age 5 or 6 years, even after the turn of the century, it would seem that an estimate of only 1 in a hundred is very low.

In dealing with these facts, it cannot be assumed that the dress and hairstyles for little boys were roughly the same at the turn of the century as those of modern times. The illustrations in and department-store catalogues, the dress-pattern instructions such monthly periodicals as The Delineator and The Standard Designer, the illustrations and advertisements in St. Nicholas, and other children's

magazines of the era, the photographs of little boys which have been reproduced in the biographies of American men

who were Hemingway's contemporaries, and the materials; file in the Bettmann Archive and other depositories all attest to contrary. There was a much greatest variety of appearance 80-90 years ago among little boys than is the

case today ay In age of innocence about infantile sexuality, the average mother would be less constrained in making choices about this matter than her. latter era counterpart would.

|

Most of the boys who were born in the United States in the years of the 19th Century and the and the first decades of the 20th Century wore dresses until they were able to walk. Only from that point onward did a majority wear clothes especially designed for boys. On formal occasions, the typical boy might appear in a navy-blue sailor outfit with white piping, or in a buttoned military tunic that was worn with knickerbockers, leggings, and a campaign hat and was commonly known as a Tommy Atkins or Rough Ridei suit, or in an elegant velvet jacket with matching knickers. Striped shirts with broad white collars and either long or short pants were a popular form of informal attire, as were overalls and long-sleeved calico shirts.

Boys who were not taken out of girls' clothes after about a year generally wore blouses and bloomers or ankle-length dresses for another 12 to 18 months. After the age of 2 1/2, however, most of these boys were also put into boys' clothes. Of the total number of little boys in the United States, no more than 10 or 15 percent were still kept in girls' clothes until they were four or five years old. Their skirts, dresses, and pinafores, moreover, were apt to be more tailored than the comparable outfits worn by little girls: in fact, some of the girlish costumes designed for boys had a

distinctly military air. Skirts with a broad box-pleat in front recalled the kilts of Scots Highlanders, while the jackets worn by boys in skirts were often trimmed with officers'straps or braid. Fewer than one out of three of the girlish costumes designed for boys over two were identical in every detail with the costumes worn by girls.

Well over half of the little boys at the turn of the century sported boyish haircuts after they emerged from infancy. Some boys wore their hair cut short, parted and slicked down, or in a full mop that was trimmed to show the ears. Others were

given what would today be called a crew cut. Still others had their hair shaped in a square-cut, above-the-ears style called Dutch- boy. On the other hand, the publication in 1886 of Frances Hodgson Burnett's Little Lord Fauntleroy had touched off a fad for shoulder-length hair

that was still being imposed upon a fair-sized minority of little boys--Thomas Wolfe among them--in the period when Ernest Hemingway was growing up. Another feminine hairstyle sometimes seen on little boys of that era was the Dutch-dolly, where the hair was cut in bangs across the forehead and

squared off on either side well below the ears. Grace was less consistent with Ernest's hairstyles. Sometimes she wanted identical styles, but not always. Ernest sometimes wore his hair in a loose, tapered coiffure that was nearly as long as his sister's hair. Interestingly she also had him in short hair almost like the modern crew cut. Her favorire though appears to have been bangs, a square-cut bob extending down well over his

ea rs, very similar to the way his sister wore her hair. Grace reportedly liked to refer to each of the children, with their Dutch boy bangs, as her sweet Dutch dolly.

One of Hemmingway's biographers is highly critical of Grace for dressing Ernest in dresses, after he was 2 years old and had learned to walk. He discusses the issue at some length:

Among many photographs of Ernest as a little boy are a number that show him looking exactly like a girl, although none of them seems to has been taken after he was 2 years old. Others show him in strikingly girlish clothes but with his hair cut boyishly short. Still others show him in boys' clothes with hair of a girlish length.

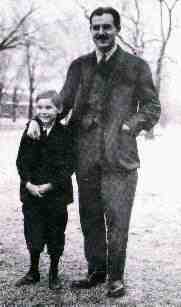

Figure 5.--Ernest by 1923 had become a published author. Here he poses with his brother Leicester wearing knickers. Their father did not approve of Ernest's work.Many different combinations of dress and hairstyle for boys were possible. Yet most of them managed to suggest in one way or another that the child in question was indeed a boy. In the age group between 1 and 2 years, perhaps as many as 20 boys in a hundred garbed and coiffed in ways that made them indistinguishable from little girls, The vast majority, however, were identifable by gender. Boys with long hair were either put into boys' clothes or into girls' clothes marked by distinctively boyish touches, while ???? who were attired in altogether girlish clothes had their hair cut short. After the age of 2 years, the number of boys who looked exactly like girls fell off to something like 5 percent, and there is some evidence which suggests that the percentage was considerably smaller. Thus, a sample composed of six hundred illustrative items drawn from widely differing sources contains only one picture of a boy between the ages of two and five whose masculinity is not readily recognizable. An illustration in the July 1897 issue of the dress-Pattern magazine, The Standard Designer, depicts a child of three or four with shoulder-length locks wearing a pleated dress with puffy sleeves, lace cuffs, and a broad lace collar. Were it not for the legend, Little Boys' Apron, beneath the picture, one would think that the child was a girl.

Ernest during his early childhood, appears repeatedly in

hair-and-dress combinations that make him look girlish. While many boys

at the time wore dresses. Many of their outfits had boyish touches

making it possible to identify their gender. This does not appear to

have been the case of the outfits Grace selected for Earnest.

One of his biographers insists that this served to set him apart to

some degree from the majority of boys of comparable age.

Interestingly, available photographs seem to show changing outfits

shifting between rather unusual outfits. While the available evidence

is not definitive, it appears that once trousers were purchased for a

boy, hr then stopped wearing dresses. There may have been a short

period before a complete new wardrobe was purchased. But this seems

to have been the likely pattern. Hemingway's biographer insists,

Not many boys of his generation, it is safe to say,

were compelled to alter their appearance as many times as

he was. For that oddity too, his mother was responsible. Yet

even odder was her elaborate pretense that little Ernest and

his sister were twins of the same sex.

Psyco-history is currently fashionable. Hemmingway's biographer writes:

In later years, she would account for her treatment of Ernest and Marcelline by saying that she had always wanted to be the mother of twins. Like Marcelline's statement that her father punished his children because he was a strict disciplinarian, it was an explanation which merely restated the problem. Of the many other possible explanations, the most plausible is that Ernest's birth had aroused memories that were painful for her of her brother Leicester's birth. Ernest, after all, had arrived a year and a half after Marcelline, just as Leicester had arrived two years after Grace. Leicester had promptly preempted his parents' attention simply because he was a baby, and later had been given other privileges-such as ownership of a bicycle- simply because he was a boy. How much nicer it would have been for Grace if she and little Leicester had been twins of the same sex. How much nicer, correspondingly, it would be for Marcelline-her mother's surrogate-if she and little Ernest could be turned into twins. Thus, she took early action to assert her authority over even the sexuality of her son.

Hemingway's biographer believes that Grace did not just want Ernest and his sister to look like twins. Marcelline's insists that her mother wanted them to feel like twins, by having, everything alike.

The children slept in the same bedroom in twin cribs. A younger children they had similar toys and games. They had dolls that were just alike and played with the same china tea sets that had the same pattern. As older

children they did more boyish things together. Grace encouraged Ernest and his sister to fish together, hike together, and visit friends together. Grace deliberately held Marcelline back a year so they could enter school together.

Ernest was sent to kindergarten in trousers (probably knickers) with suspenders. After they

began school, Grace no longer dressed alike, except for similar coats and knited caps. Hemingway attended Oak Park and River Forest High School (1913-17). He was active in sports, including boxing, track and field, water polo, and football. He did well academically. He liked English and had good grades. He and Marcelline performed in the school orchestra. As a junior year he sined up for a journalism class. The teacher Fannie Biggs designed the class to operate as a newspaper office. It was to have a major impact on the young Hemingway.

The United States declared war on Germany (April 1917). Hemingway graduated from highschool a few months later. He saw a Red Cross recruitment effort and signed on to be an ambulance driver in Italy (early-1918). The experiebnce woukld have a major impact on his life.

Hemingway after the War returned home to Michigan. Like many returning veterans, he had trouble finding a job. His first job was as a reporter for the Co-operative Commonwealth, a glossy paper monthly magazine put out by the Co-operative Society of America. He didn't earn much ($40 per month) and was not very happy with

the assignments he was given.

Hemmingway met Elizabeth Hadley Richardson after retuning from Italy. They met in a friends apartment. He was enchanted by her. Elizabeth was older than Earnest. She was 28 years old, but very innocent. She had been educated at Mary Institute, a private school for girls. Although older than Ernest, she was still living at home and very naieve and inexperience. She was called Hadley by the family. They married (September 3, 1920). They married in a country church at Horton Bay. Their wedding feast was a modest chicken dinner. The honeymoon was at Ernest's father's house at Bear Lake. It was here that Ernest had spent most of his boyhood summers. They rented an inexpensive top floor apartment. It has been described as "grubby and depressing", but it was cheap. Hemingway had quit his job and begun writing. They lived on Hadley's trust fund. Hemingway began writing and sent in article to the Toronto Star. They saved their money for a planned trip to Europe.

They departed for Paris (January 9, 1922).

They returned to America so their first child, John Hadley Nicanor Hemingway, could be born in America. He was called Jack within the family. Hemingway by this time had become a recognized author with aricle published in important magaziines. He was thus finally earning a little money. He also wrote feature rticles for the Star Weekly. He decided to give journalism up and returned to Paris with Hadley anhd the baby.

Hemingway, his wife and baby Jack returned to Paris (1924). They traveled widely (Austria, Spain and Switzerland). Hemingway wrote another The Sun Also Rises and ther Torrents of Spring during their marriage which lasted 5 years.

Hemmingway had an affair with Vogue editor Pauline Pfeiffer. When Hadley learned of it, she insisted on a separation. He dedicated The Sun Also Rises to Hadley and John. He explained that it was 'the least he could do'. He gave all the royalties to Hadley. The two were devestated by the subsequentb divorce (1927)as they both deeply cared for each other.

Hemingway had three childre. The first was John Hadley Nicanor Hemingway (1923-2000). His mother was Heminways first wife Elizabeth Hadley Richardson. The couple had returned from Europe so the baby could be born in America, but he was born in Toronto, Canada. He was usually called Bumby or Jack. None other than Gertrude Stein and her partner, Alice B. Toklas, were his godparents. He would lead an even more adventuresome life than his father. He joined the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) during World War II. This was the United States wartime spy agency and predecessor of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). He worked with the French Resistance. He was wounded and captured by the Germans Nazis behind the front lines in the Vosges Mountains where the Germans were still resisting (October 1944). He could have been shot, but was instead held as

a prisoner-of-war at Mosberg Prison Camp until he was liberated (April 1945). Hemingway's second son was Patrick (1928- ) who he had with his second wife, Pauline Pfeiffer. She was the cause of the breakup with Hadley. Their second son was Gregory (1931–2001). Hemingway was very close to the boys and is particularly known for taking them big game fishing in Cuba.

Kenneth S. Lynn, Hemingway, (New York: Fawcett Columbine, 1988).

Leicester Hemingway, My Brother Ernest Hemingway, (Crest Book: Greenwich, 1961).

Navigate the Boys' Historical Clothing Web Site:

[Return to Main biography page]

[Return to Main United States page]

[Introduction]

[Activities]

[Biographies]

[Chronology]

[Cloth and textiles]

[Garments]

[Countries]

[Topics]

[Bibliographies]

[Contributions]

[FAQs]

[Glossaries]

[Images]

[Links]

[Registration]

[Tools]

[Boys' Clothing Home]