The American Revolutionary War: Coming of War

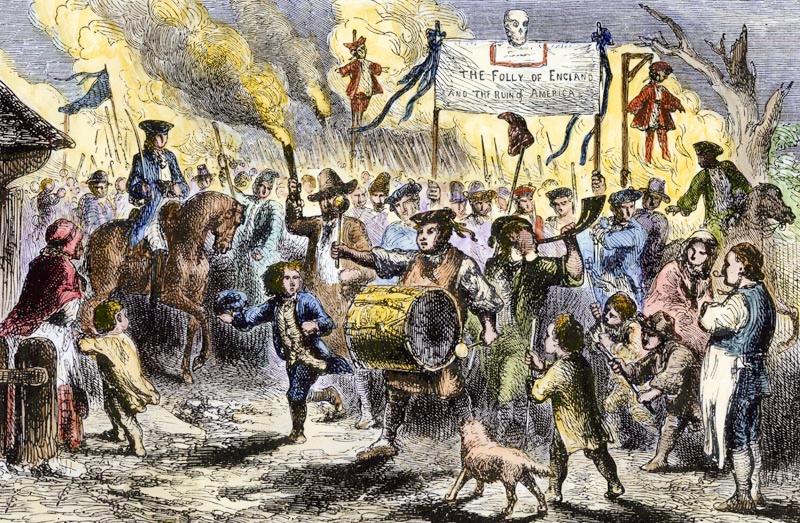

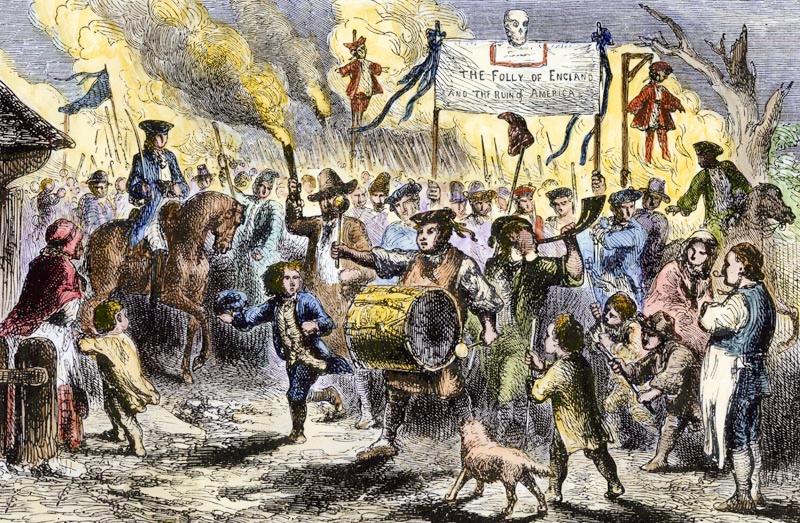

Figure 1.--This colored illustration depicts the Stamp Act Riots in Boston (1765). It was originally published in the' Historical Scrap Book' (Cassell and Company, 1880). The Stamp Act was one of many British efforts to get the cololnists to pay part of the cost of the French and Indian War.

|

|

The Revolution was a war that the British could have easily avoided had King George and his advisors been willing to show the some flexibility. In many ways it seems difficult to understand the depth of colonial dissatisfaction with the British. The two central issues in the war were: !) the authority of the colonial legislatures and ultimately the power to tax and 2) British restrictions on western movement and colonial land claims beyond the Appalachian Mountains. Had Britain not attempted to dilute the prerogatives of the legislatures it seems likely that the colonists would have never been pushed toward common action and instead been more focused on the individual and in many ways conflicting interests. Furthermore, many in Britain objected to the War and a minority of Americans wanted independence at the time the war began. At the onset probably less than a third of American wanted independence. Surely at least a third, probably more saw themselves as Englishmen living in America and loyal subjects of the King. The World was a dangerous place. Most Colonists were of English stock and many looked on England as home. Many also welcomed the protection of the British Empire and had no desire to leave, as long as they could have local self government. This loyalty to the British Empire was especially strong among the privileged class who were eventually to become the major Patriot leaders, men like Washington, Adams, Jefferson, Hancock, Franklin, and many others. The same was true in the South among the planter class. The question of how men who considered themselves British came in a relatively short period of time to take up arms against Britain is a fascinating question. A good example here is wealthy planter, Landon Carter, of Virginia. We mention him because he kept a diary and one can trace his thought process as he moved slowly from ardent monarchist to reluctant rebel. [Issac] For him and many others, the turning point was the Stamp Act. These were men who not only feared existing in a world without the protection of the Empire, but also facing future challenges to their privileged lives from the poor and uneducated that constituted the bulk of the population. It is no accident that the American Republic resulting from the War was a very undemocratic republic—albeit mote democratic than any other country at the time. (The result is still with us today in that George Bush became President when more Americans voted for Al Gore.) Only incredibly arrogant policies pursued by the King and his compliant Parliament gradually turned American opinion toward Independence. [Ketchum] In this regard, Lord North's intemperate remarks played an especially important role. [Green, p. 8.]

British Leadership

The Revolution was a war that the British could have easily avoided had King George and his advisors been willing to show the Colonists some flexibility. Parliament was intent on the outlook that the Colonies existed to benefit Britain. As a result, regulations limited manufacturing and trade with other countries. The American economy essentially was to benefit Britain not the colonists. And in particular, Parliament (Westminister) was not about to ceded the hard won principle of parlimentary supremecy to colonial legislatures.

Central Issues

The two central issues in the Revolutionary War were: 1) the authority of the colonial legislatures and ultimately the power to tax and 2) British restrictions on western movement and colonial land claims beyond the Appalachian Mountains. The perogatives of the Colonial legislatures had developed during the 17th century when England was absorbed with the Civil War and its aftermath. Little attention was given to the colonies which developed with little attention by either parliament or the monarcy. Thus by the 18th century, the perogatives of the colonial legislatures were well established and there was little experience with direct British rule. British actions to play a more direct role were thus seen by many were seen as a attack on their established perogatibes. Had Britain not attempted to dilute the perogatives of the legislatures it seems likely that the colonists would have never been pushed toward common action and instead been more focused on the individual and in many ways conflicting interests. The Western issue would have required a change in British policy.

British Opinion

Many in Britain objected to the War. The Whigs in particular symphathized with the Colonists. This was not, hoever, the faction that dominated Parliament and was the faction supported by King Gerorge. The modern political alignment of Tory and Whigs began to take shape during the reign of George III (1760–1820). There wasca a shift in the meanings to the two words. Real political parties did not yet exist in Britain. There was no Whig Party, what existed was loosely associated aristocratic groups which had begun to shift from land to commerce and gas pronounced family connections which affected both patronage and influence. There was also no formal Tory Party, but has been called Tory sentiment, involving tradition and temperament among supportive families and social groups. They were referred to as the King’s Friends. It was from this grouo that the King preferred to draw his ministers. He was especially close to Lord North (1770-81). Notably this was the period in which relations with the colonies began to deteriorate. Whig leadeers like Edumnd Burke and James Fox were sympathetic to the Colonists' grievances. Formal party strutures began to take shape after 1784, when deep political issuesbegan to stir public opinion. The American Revolution was perhaps the first of these iussues.

Evolution of Colonial Opinion

A minority of Americans wanted independence at the time the war began. At the onset probably less than a third of American wanted independence. Surely at least a third, probably more saw themselves as Englishmen living in America and loyal subjects of the King. The World was a dangerous place. Most Colonists were of English stock and many looked on England as home. Many also welcomed the protection of the British Empire and had no desire to leave, as long as they could have local self government. This loyalty to the British Empire was especially strong among the privileged class who were eventually to become the major Patriot leaders, men like Washington, Adams, Jefferson, Hancock, Franklin, and many others. The same was true in the South among the planter class. The question of how men who considered themselves British came in a relatively short period of time to take up arms against Britain is a fascinating question. A good example here is wealthy planter, Landon Carter, of Virginia. Wemention him because he kept a diary and one can trace his thought process as he moved slowly from ardent monarchist to reluctant rebel. [Issac] For him and many others, the turning point was the Stamp Act. These were men who not only feared existing in a world without the protection of the Empire, but also facing future challenges to their privileged lives from the poor and uneducated that constituted the bulk of the population. It is no accident that the American Republic resulting from the War was a very undemocratic count. (The result is still with us today in that George Bush became President when more Americans voted for Al Gore.) Only incredibly arrogant policies pursued by the King and his compliant Parliament gradually turned American opinion toward Independence. [Ketchum] In this regard, Lord North's intemperate remarks played an especially important role. [Green, p. 8.]

Colonial Disatisfaction

In many ways it seems difficult to understand the depth of colonial disatisfaction with the British. The American colonists were the freest people on earth and the most affluent. Average living conditions were better n America than in England. The Colonists were also lightly taxed. Estimates vary, but some authors suggest that the colonists only paid a quarter of the taxes paid by peope in England. The Colonists objected to the tax on tea and the Stamp Act, yet in England there was a long list of items that were taxed. [Weintraub] Thus the English were paying taxes for the very expensive proposition of garisoning America. The Americans through smuggling were able to import most items free of any duty. The argument of course was made by the Colonists that they had no representation in the British Parliament, but of course with the "rotten buroughs" of Brotish electoral politics neither were many Englishmen. There were many English people that were sympethetic to the American cause, but many others supported the King. Sammuel Johnson called the Colonists sophists. He wrote, "We here the loudest yelps for liberty among the slave drivers of negros".

Political tensions began to rise in North America as the British after the French and Indian Wars began to give more attention to governing North America rather than leaving it to the the Colonial Legislatures. A primary concern was paying off massive debts incurred in the French and Indian and wider Seven Years War. Parliament wanted the Colonists to assume part of the cost of the War as well as the administratiion and protection of the colonies. Sir Thomas Gage was the British miitary commander of North America. Much of the British force of 10,000 men in the afermath of the French and Indian War was deployed on the Frontier. They were used to quell Potianc's rebllion (1763). The British Prliament passed the Stamp Act as the first major effort to raise revenue (1765). The new tax was imposed on every piece of printed paper. The actual tax was small, but the Colonists saw it as a dangerous presidence. Until this point taxes were levied by the colonial legislatures. Now Parliment in which the Colonies had no representation was imposing taxes. Gen. Gage as a result of the rising tensions began shifting troops from the Frontier to colonial cities like New York City and Boston. As the number of soldiers stationed in cities grew, the need arose for providing food and housing. Parliament passed the Quartering Act, permitting British commanders to quarter men in private residences without the consent of the home owner (1765). This outraged the colonists. And as the Coloniots anticipted, the Townshend Revenue Act followed (1767). Parliament placed taxes on glass, paint, oil, lead, paper, and tea with the goal of raising £40,000 annually to pay for the administration of the colonies. This created an even more vocal opposition than the stamp Act. The reaction turned violent in Boston. Massachsetts and Boston in particulr would prove the crucible of revolution. The Massachusettes Bay colony ws the most radicalized of North American colonies, but similar opinions were prevalent throughout the colonies. British Customs officials in Boston impounded a sloop owned by one John Hancock, a prominant Boston merchant (summer 1768). He was believed to be violating trade regulations whichb he indeed was. A crowds agthered in protest and mobbed the Customs Office. The officials there were forced to flee to a British Warship in the harbor. The British wre forced to bring in some 4,000 troops from England and Nova Scotia to reoccupy Boston (October 1, 1768). Bostonians offered no resistance at this time. Instead they developed new tactics. They stopped buying British goods. Merchants in other colonies followed suit. British imports fell sharply. Using 4,000 troops to occupy Boston with only about 20,000 people seems an overreaction. And it proved to be a major mistake. It was also costly given that the whole idea of the Townsend Act was to raise revenue to pay for colonial administration, not increase spending. But costs inside, it created wide-spread resentmnt in Boston. Bostonians were forced to house the soldiers in their own homes. This turned even many pro-British colonists against the British making the ciy virtually ungovernable. A violent clash was inevitable and it soon came. A protesting crowd including individuals who had been drinking confronted a small group of British regulars. The result was the Boston Masacre, at least that is how Colonial newspapers described the ecounter. What ever the descriotion, five Bostonians were left dead on the streets. The Colonists were outraged.

Sources

Green, James A. William Henry Harrison: His Life and Times (Garrett and Massie: Richmond, Virginia, 1941), 536p.

Issac, Rhys. LLandon Carter's Uneasy Kingdom: Revolution and Rebellion on a Virginia Plantation (Oxford University Press, 2004), 423p.

Ketchum, Richard M. Divided Loyalties: How the American Revolution Came to New York (Henry Holt, 2002), 447p.

Weintraub, Stanley. America's Battle for Freedom, Britain's Quagmire, 1775-1785.

CIH

Navigate the Children in History Website:

[Return to Main Revolutionary War page]

[Return to Main military style page]

[Introduction]

[Biographies]

[Chronology]

[Climatology]

[Clothing]

[Disease and Health]

[Economics]

[Geography]

[History]

[Human Nature]

[Law]

[Nationalism]

[Presidents]

[Religion]

[Royalty]

[Science]

[Social Class]

[Bibliographies]

[Contributions]

[FAQs]

[Glossaries]

[Images]

[Links]

[Registration]

[Tools]

[Children in History Home]

Created: 8:08 AM 9/24/2019

Last updated: 8:08 AM 9/24/2019