Soviet Collective Farms

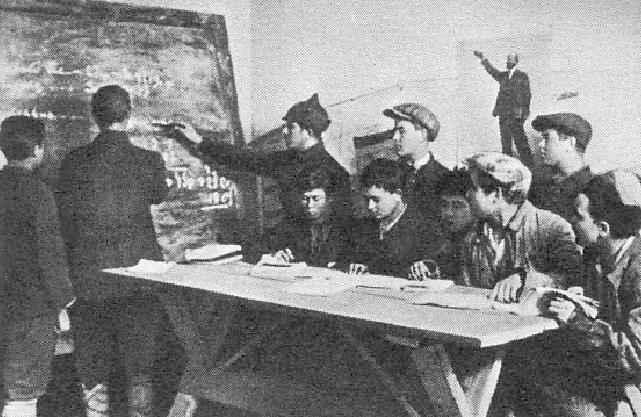

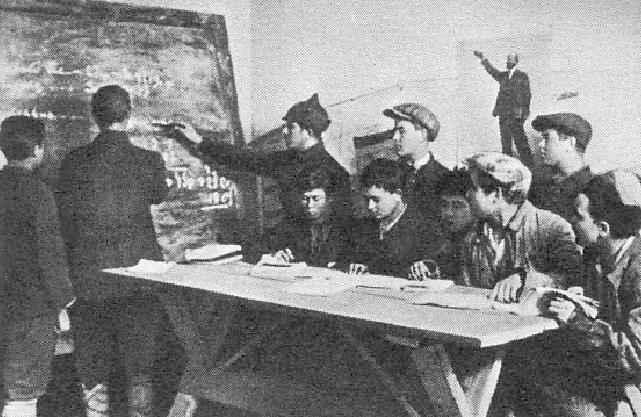

Figure 1.--This obviously staged photograph appears to show a class on a collective farm. Unfortunately we do not know when or where it was taken. Note that the teacher wears a Red Army cap. I am not sure if this means that at some early collectives soldiers were recruited as teachers.

|

|

A Soviet collective farm was a cooperative agricultural enterprise which was operated on state-owned land by peasants from families who belonged to the collective. The Russian term was kollektivnoye khozyaynstvo (kolkhoz).

The kolkhoz members were paid as salaried employees as if they were factory workers. The salary was based on the on the quality and quantity of the labor performed. The kolkhoz was conceived in the Soviet Union as a voluntary association of peasants. It was in keeping with Soviet Communist ideology which emphasized collectivization over private property. The peasant farmers of the Soviet Union, however wanted nothing to do with collectivizstion which had to be forced upon them. We have little information at this time as to the new collective farms and life on the farms. We are not sure just who was put in charge of the collectives. We do not know what kind of facilities were built or accomodations for the families. Apparently there was some attempt at mechanizing agriculture through the new collectives. This would seemingly increase production. More significant apparently was the elimination of many competent farmers (the so-called kulaks) and undermining the work ethic created by actual ownership. The new collectives had schools, but we know little about them at this time. There are propaganda impages of the collectives, but we are judt beginning to find reliable reports about conditions on these collectives and how it changed over time.

Definition

A Soviet collective farm was a cooperative agricultural enterprise which was operated on state-owned land by peasants from families who belonged to the collective. The Russian term was kollektivnoye khozyaynstvo (kolkhoz).

The kolkhoz members were paid as salaried employees as if they were factory workers. The salary was based on the on the quality and quantity of the labor performed.

Early Soviet Kkolkhozy

The kolkhoz was conceived in the Soviet Union as a voluntary association of peasants. It was in keeping with Soviet Communist ideology which emphasized collectivization over private property.

Agricultural production after impressive gains durng the NEP of the 1920s declined in the 1930s. This was in sharp contrast to rising industrial production and wholly the result of Stalin's decession to end individual peasant propretorship (1929-31). We do not fully understand Stalin's thought processes here. There may have been an element of idelogical purity involved. The organization of the collective proved useful in fighting the NAZI invasion. The principal reason, however, appears to be that private proprietors were an independent interest group outside his control and he wanted total control of not only the Sovet state, but of Soviet society as well. The mechanisms used were brutal. Successful peasants were vilified as Kulaks. Most were forced into collectives others were deported to Siberia where many died. Resistance flared. Many peeasants slaughtered their livestock rather than turn it over to the collectives. [Wells, pp. 960-961] The Soviet livestock industry did not recover until well after World War II. Resistance was espcially pronounced in the. and was brutally supressed by the NKVD. The center of resistance was the Ukraine. There a terrible famine not only resulted, but was enginered by Stalin.

Result

The kolkhoz as a result of Stalin's brutal collectivization programs in a few short years during the early-1930s became the dominant form of agricultural enterprise as the result of a state program of expropriation of private holdings, almost entirely peasant holdings because the large landed estates had been broken up early in the Revolution. Collectivization did as Stalin desired, successfully increase state control over the lives of the peasantry. It did not, however, increase production. Agricultural harvests declined substantially. Tsarist Russia had been a major expoter of grain. This was no longer the case for the Soviet Union.

Soviet Law

Soviet kolkhozy/collective farms were were legally organized as a production cooperative each had a charter, which was a tandard statement prepared by Soviet authorities and had the force of law. To avoid problems created by differences in the charters adopted by early kolkhozy, a Model Charter was approved (1935). The Model Charter text was a paragon of democratic organization and cooperative principles and free assovciation. And was also a complete fiction in reality as was usually the case in Soviet law. It describes the kolkhoz as a “form of agricultural production cooperative of peasants that voluntarily unite for the purpose of joint agricultural production based on ... collective labor.” It describes the operation of the kolkhoz as being "managed according to the principles of socialist self-management, democracy, and openness, with active participation of the members in decisions concerning all aspects of internal life”.

Each kolkhoz was theoretically giverned by an independent eneral assembly and 'democratically' elected managers. I reality they for the most part simply cast aro-forma vote approving the plans, targets, and decisions made by the Soviet kolkhozy district and provincial authorities.

The Soviet collective farm as organized under Stalin's rule was very different than a cooperative. The land in the Soviet Union had been nationlized by the Bloshevicks (1917), but pesants had been allowed to farm the land they had formerly owned or seized from landlords or the large landed estates. This was the land seized during Stalin's collectivization process. The non-land assets were owned by the collective and not the individual members. This included their homes and garden plots.

Renumeration

The kolkhozy members were not state employess. They did not recive a state salary. Rather they were paid from for their lsbor from the earnings of the kolkhozy. This was largely determined by the state which both set prices paid for harvests and thhe cost of inputs like seed, fertilzer, cost of mchiery, fuel, ect. Renumeration was at first very low as one of Stalin's goals was to transferc resources from the counyryside to the cities where he was building a newcindudtrialn economy.

The New Soviet Serfdom

The kolkhozy members were by no means freely associated labor. They were forced into collectivization. Stalin's campaign of forced collectivization relied on a hukou system to keep farmers tied to the land. And once there they were not allowed to freely leave unless they received permission to do so which was difficult. This included children. Soviet law required that the children born on a collective farm were required to work there as adults unless they obtained permission to leave. [Humphrey, p. 14.] Readers will of course realize this was much like Tsarist sefdom which tied serfs to the land. The serf had to obtain permisdion of the landowner ton leave. Thus in a very real way, the Soviet kolkhozy system was essentially state serfdom. And if the kolkhoz member did manage to leave, they received no compensation for their theoretic share of kolkhozy assetts.

Poor Performance

Stalin assumed that by ending private onership the magic of sovialism would increase agricultural ouput. Murdering the Kulaks and Ukranian peasantry to Stalin meant getting rid of not only disloyal people, but inefficent louts that holding the Soviet miracle back. And by mechanizing agriculture with tractors Stalin had no dount that agrivultural harvesrs would soon reach unbelievable levels. To his asstonishment just the opposite occurred. Agricultural output fell. Collectivization actually caused poor performance. It has been referred to as a form of 'neo-serfdom'. The Communist atate bureaucracy had aimoly replaced the former Traist landowners. [Faonsod, p. 570.] And they had killed many of the most produvctive farmers in the country. And the productivity of Soviet farms would reflect this. The new state and collective farms were overseen by outside directives who had no knowledge of local growing conditions or took them into maccount. Nor dis they see the need tom incentivize farm workers. They required farm wirkers to deliver much of their produce for nominal payment. The collective farms may have had tractors, but the farm workers had no incentive to work--something Marrxist ideology did not deem as particulaly important.

State Contol

The Soviet state controlled the kolkhozy. The primary control was appointing kolkhoz chairmen, only nominally elected. There were also political units in the machine-tractor stations (MTSs) which furnished heavy equipment in return for payments in kind of agricultural harvests. This was not changed in 1958.

Family Life

Although the state owned the land, the peasants were allowed to retain the family structure and living arrangements were not communal. In many cases the kolkhoz members moved into the homes of the former peasnt families that were deported or perished in the Famine.

We have been able to find very little information at this time as to schools the kolkhoz children attended. We are not even sure about rural schools in rural areas before the kolkhozy were established. There were village schools. Depending on location, these are the schools the children first attended. There were few school busses at the gime, so the children at the more isolated kolkhozy would have trouble getting to village schools. Apparently some kolkhozy began setting up their own schools. Many kolkhozy were at first reltively small. Some would have had trouble maintainung small primary school. And we are nure who paid for the teacher and costs of the schools. Nor are we sure about what happened after the children finished primary school. We do not know how many of the children went on to secondary schools. Even larger kolkhozy could not have supported a secondary school. This meant that the children presumably would have had to attend some kind of boarding school, but we have no information at this time as to how common this was. There were apparently major changes after world war II. An amalgamation prigram created larger kolkhozy which were better ablecto support schools (1949). More changes came after Stalin died (1953). The Government gave the kolkhozy permission to establish non-farm cooperative industries. Large numbers of the kolkhozy did so choosin activities they were already inviolved with on amall scale to support the kolkhoz's needs. They began operating brickyards, carpentry shops, electric stations as part of a wider kolkhozy association. This substantially raised income levels at the kolkhozy. The Government required that the kolkhozy build their own schools, infirmery, bathouses, recreational, club houses, and other facilities. (We arec not sure if this was new legislation or was enforced from the brginning.) One sourcee reports that the kolkhozy in the the Ukrainian SSR built, on their own, 720 village schools, during 1953-58.

We are not entirely sure what happened at the collective farms during World War II. Stalin of course ordered a scorced earth campaign, buring crops and equipment. We do not know to wgat extent this was done at the various collectives. This may have varied reggionslly. Nor do we know if the people on the collective farms stayed or attempted to escape deast. We also do not know just what the Germans did when they reached the collectives. Ans we are not sure to what extent the collectives aided the partisans. The Germans also ececuted a scoarched earth campaign as they retreated west. We suspect very little was left on the collcted frms, but here we simply do not know.

Post-War Changes

The Soviet Government after World War II began a process of amalgamation, merging smaller kolkhozy to form larger units (1949). The size increased from 75 families to about 340 households by 1960. The Government abolished the MTSs (1958). The enlarged kolkhozy assumed the responsibility for buying anmd maintaing their own heavy equipment. The Government adjusted the quota system (1961). Instead of being set by a central authority, quotas were negotiated with the State Procurement Committee. The Government did set plan goals for each region. The kolkhozy sold their harvests to state agencies at pre-determined prices. Harvests exceeding the quotas and from family garden plots was sold in the kolkhoz market. Here prices the farm workers could command for thebproduce of theor small plots were determined according to supply and demand.

Family Plots

And at a very early point, each family was alloted garden plots. Only during the first years of collectivization when family garden plots anned. Notably, this was a period of famine with millions dying. [Gregory, pp. 294–95 and 114.] These plots were variously referred to as family, household or vgarden plots. This was at first for personal consumption. These garden plots respresented a very small part of the kolkhozy land. Soviet data shows that 1.1 percent of the land in collective farms was turned over to family plots, only a small portion of Soviet farms (1928). And a larger, but still small area after collectivzation -- 3.5 percent (1940). [Narodnoe ..., p. 240). . Eventually the collective workers were allowed to sell theor produce in local markets. While the area involved was very small, they came to account for a very substantial portion of Soviet production of many important commodities. After the War as the Soviet Union recovered from the War, the family garden plots although accounting for a minisule portion of cultivated area, private plots produced a huge share of the country's meat, milk, eggs, and vegetables. These plot while never more than 4 percent of arable Soviet land, yielded an amazing quarter to a third of of the country's total produce. The simple fact was that private plots were more than 8-12 times as productive as the collective farms. Private plots became an important source of farm income for rural households--usually more than they receivedvin wages from the collectives. One study od Soviet agriculture revealed that kolkhoz members received 72 percent of their meat, 76 percent of their eggs and most of their potatoes from their small family garden plots. urplus products, as well as surplus livestock, were sold to kolkhozy and sovkhozy and also to state consumer cooperatives. Many aithors believe that official Soviet statistics under-represent the total contribution of these private plots. [Nove, pp. 116–18].

One might have thought that numbers like those produced from the family garden plots would have caused Soviet leaders to reassess their thinking and reconsider Marxist orthodoxy, but they did not. Anyone making such suggestions was putting himself in the crosshairs of the NKVD and could be either shot or sent off to the Gulag. And this did not change after Stalin's death (1953). After Kkruschev's De-Stalinizarion campaign, the NKVD became the KGB and the lvel ofrepression eased. The Terror ended amd the Gulag began to be disasemlbed, but there was no relaxation of Marxist orthodoxy. Kkruschev did not believe in terror and mass murder. He did believe in Communism. There would be no Deng Xaoping in the Soviet Union to introduce market reforms (private ownership and capitalism). Which is why the Soviet Union no longer exists today and China prospers. This is not to say that there were not efforts at reforms. Therevwas a major effort to bring marginal land into priduction, especially in Central Area. The resulkt was masive enviriomental damafe. Many reformn poprigrams were announced. None of them included privitaztion and market reforms. Nor were weak worker incentives and managerial autonomy addressed. This would only come slowly after the implosion of the Soviet Union (1991).

Other Countries

After World War II, collective farms were introduced by the Soviets in the Eastern European countries. This was also done in China and the other Asian countries. Only in North Korea was in done under Soviet supervision. Collectivization was also conducted in Cuba. We do not yet have information on Nicaragua. The system introduced differed in many respects in these different countries. The largest was Russia with a long historical experience. The others except the Baltics were not countries thst have been independent in recnt historical times. We do not yet have detailed information, but it is an interesting subject we want to persue.

Privitization

With the dissolution of the Soviet Union (1990–91), 16 independent counties were created. A few were countries aprocess of privitization began. This varied widely in the 16 post-Soviet states. In some post-Soviet countries like the Baltics, the kolkhozy, have been completely privatized. In others like Belarus they continue to operate. We even note school children being forced to work on them.

Sources

Fainsod, Merle (1970). How Russia is Ruled Revised ed. (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1970).

Gregory, Paul R. and Robert C. Stuart. Soviet Economic Structure and Performance (New York: Harper Collins, 1990).

Humphrey, Caroline. Karl Marx Collective: Economy, Society and Religion in a Siberian Collective Farm (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1983.

Narodnoe khoziaistvo SSSR 1922–1972 (Moscow: 1972).

Nove, Alec (1966). The Soviet Economy: An Introduction (New York: Praeger, 1966).

Webs, H.G. The Outline of History: The Whole Story of Man (Doubleday & Company: Ne York, 1971), 1103p.

CIH

Navigate the Children in History Website:

[Return to Main Stalinist assault on the peasantry page]

[Return to Main Great Patriotic War page]

[Return to Main Soviet school page]

[About Us]

[Introduction]

[Biographies]

[Chronology]

[Climatology]

[Clothing]

[Disease and Health]

[Economics]

[Freedom]

[Geography]

[History]

[Human Nature]

[Ideology]

[Law]

[Nationalism]

[Presidents]

[Religion]

[Royalty]

[Science]

[Social Class]

[Bibliographies]

[Contributions]

[FAQs]

[Glossaries]

[Images]

[Links]

[Registration]

[Tools]

[Children in History Home]

Created: 4:12 PM 3/14/2005

Last updated: 1:55 AM 10/17/2019