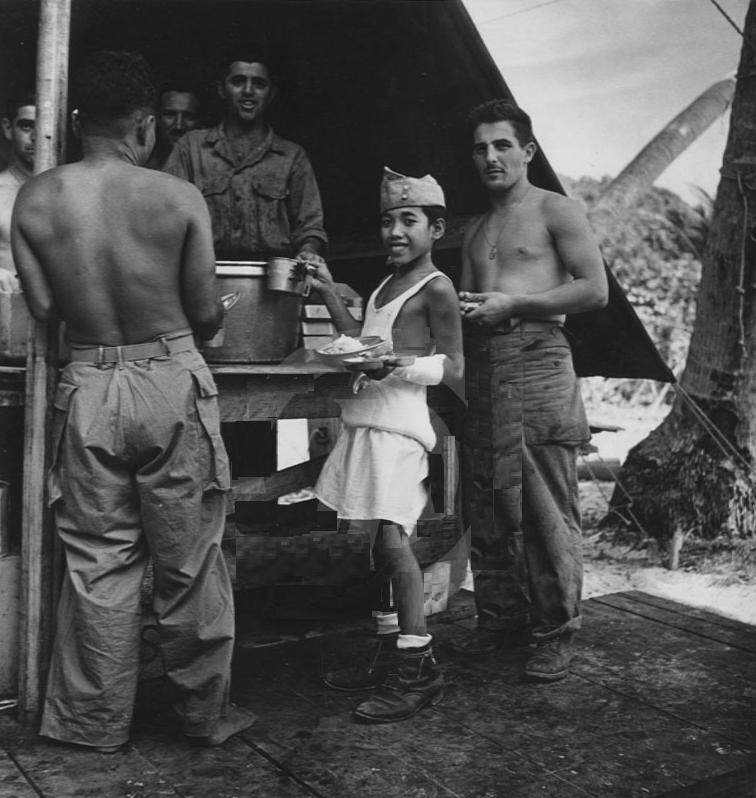

Figure 1.-- This press photo was taken on Kwajalein several months after the invasion. The caption read," He's not exactly a member of the U.S. Army, but the nearest thing to it. This native boy joined the chow line on Kwajalein to try GI food." |

|

The U.S. Marines proved in the Gilberts that cut off island garrisons could not hold. The Marines and Army supported by the U.S. Navy next assaulted the Marshall Islands. They were further west and closer to the Marianas, but still the Imperial fleet was not expected to intervene even though it would put Truk in jepordy. Both the Navy and Marines learned from their bloody experiences in the Gilberts. Naval gunners and airmen practiced in Hawaii. Better landing craft were available. Nimitz decided to focus the attack on Kwajalein and simply bypass most of the other islands. Efforts were also made to improve radio commuications between the Marines and the fleet with air and naval spotters going ashore with the Marines. The Marines this time had greater fire support as well as heavily asrmed amtracks. Naval gunfire and air assaults raked Kwajalein for 3 days with far greater accuracy than in the Gilberts. Frogmen blew holes in the reef at key locations. The Marines landed (January 31). Artillery was set up on offshore islands. Kwajalein was taken in 4 days with less than 2,000 casualties. The smaller islands were subjected to air attacks and naval gunfire rendering them impotent. This success and the lack of any indication that the Imperial Fleet would intervene caused Nimitz to move up the assault on Eniwetok from May 1 to February 17. Forces were available because Kwajalein proved less costly than abticipated and the other islands had been bipassed. Eniwetok was 1,000 miles further west, but as dexpected the Imperial Fleet did not intervene. The Americans landed 8,000 men, two reinforced regiments (February 17). They were opposed by 2,000 Japanese. Mistakes were made, especially with the naval gunfire. The Japoanese resisted tenaciously, almost to a man. But the island was in American hands (February 22). The cost was less than expected--about 1,000 casualties including 300 killed.

The Imperial Japanese Navy and Army high commands were staggered by thec defeats inflicted on them by the Americans. Japanese planners had not anticipated an American offensive intil well into 1943. The Midway defeat was so staggering, that for several months the Navy did not even inform the Army of what had transpired. The Guadacanal offensive was so unexpected that neither the Navy or Army understood it was not a raid, but an American offensive. The air an naval losses in the Solomons and New Guinea were staggering and occurred at a time that the United States was just beginning to field imporyant new firces. The Imperial High Command decided that it could not continue to slug it out with the Americans in forward positions (September 1943). Rather the Solomons, New Guinea, Gilbert, and Marshall Islands would be conceded to the Americans. There remaining forces would regroup for the defense of the Philippines and Marianas to stop the Americans from reaching the Home Islands. The Marianads would be defended because air bases there could be used by the new B-29 Superforts to bomb the Home Islands. Whuke the Gilbers and Marshalls were seen as non-essential, the High Command decided to reenforce them strongly to extract the maximum of American blood. It was now clear Japan could not win the War, but by making the American advance as costly as possible, the Japanese hope that the Americans could be persuaded to make peace. The problem for the Japanese was getting the reenforcemrnts to the Gilberts and Marshalls and supplying them once there. The American submarine campaign was steadily reducing the Maru fleet. And Americam surface and air patrols were intercepting Japanese shipping in forward areas. As a result, although Japan has a very substantial army, the Pacific islamd campsigns were fought with relatively small forces.

The U.S. Marines proved in the Gilberts that cut off island garrisons could not hold (November 1943). The Japanese were able, as hoped, to extract a heavy price at Tarawa. The next target for the Marines and Army supported by the U.S. Navy next would be the Marshall Islands. They were further west and closer to the Marianas, but still the Imperial fleet was not expected to intervene even though it would put Truk in jepordy. Both the Navy and Marines learned from their bloody experiences in the Gilberts. Naval gunners and airmen practiced in Hawaii. Better landing craft were available. Efforts were also made to improve radio commuications between the Marines and the fleet with air and naval spotters going ashore with the Marines. The Marines this time had greater fire support as well as heavily armed amtracks.

vThe Pacific Fleet was no longer operating on a shoe string. The Fifth Fleet by early 1944 had been converted into the most powerful naval force in the history of warfare. Sprance and Halsey who alternated command were just beginning to understand the capabilities of the fleet. There was more than sufficent forces to take the Marshalls, especially as the Imperial Fleet was no going to intervene. The Japanese air capability was limited. Most important, the Japanese could not hide their airfields or on the small islands their planes. This a carrier strike could cripple Japanese air forces, leaving them incapable of striking back at the carriers.

The U.S. Fifth Fleet for the Marshalls invasion (fall 1943) had 6 heavy, 5 light, and 8 escort aircraft carriers available. AThere were also 12 battleships (including some raised from Pearl Harbor) as wll as five new ships, and nine heavy and five light cruisers. In addition were 56 destroyers. As the Imperial Navy was not going to intervene, this potent foirce could be used to bombard the islands. And worst still, more ships were reaching the fleet each month

The infantry landing force for the Kwajalein invasion would be Fifth Fleet's Fifth Amphibious Force, commanded by Rear Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner. He was by now an experienced amphibious force commanddr. His job was to get the infantry on the beach. Turner commanded the naval assets, the transport ships, cargo vessels, landing craft, and new landing ship docks (LSDs). In addition he commanded the destroyers, escort carriers, cruisers, and battleships that would support the assault. Land-based naval aircraft were of lesser imortance and under the command of Rear Adm. John H. Hoover. General Holland M. Smith, commander of the V Amphibious Corps, already a legendary figure, controlled the ground forces committed to the operation. These included the newly organized 4th Marine Division (training state-side), the independent 22d Marine Regiment (from Samoa); the the Army's 7th Infantry Division (which had participated in the battle for Attu and Kiska); and the 2d Battalion, 106th Infantry, 27th Infantry Division. The rest of the 106th Division and the 111th Infantry were leld back as a seaborne reserve. The landing commanders were: Maj. Gen. Harry Schmidt (4th Marine Division), Maj. Gen. Charles H. Corlett (the 7th Infantry Division), Col. John T. Walker (22d Marines), and Lt. Col. Frederick B. Sheldon (2d Battalion, 106th Infantry).

Kwajalein was the headquarters for the Japanese 6th Base Force. It was the Japanese administrative center of the islands. The ciommander was Rear Adm. Monzo Akiyama. This was one of the administrative units of the Japanese 4th Fleet, based on the island of Truk in the Carolines west of the Marshalls. Truk was the strongest Japanese bastions in the Pacific and the primary fleet ancorage for operations in the South Pacific. After the Japanese decesion to pull back (September 1943), they begn to withdraw the fleet from Truk. The 4th Fleet was commanded by Vice Adm. Masashi Kobayashi, who was responsibe for the Gilbert Islands, Nauru, and Ocean Island as well as the American islands of Wake and Guam,

Admiral Kobayashi by the time of the Gilbert and Marshalls campsaign commanded a fleet that had largely ceased to exist. The old Japanese light cruisers Naka, Isuru, and Nagara and the 22d Air Flotilla were the major combat forces. Both lsuzu and Nagara were hit by Americanm naval air strikes in the run up to Flintlock and had to be withdrawn for repairs. The total Japanese force in the Marshalls Marshalls amounted to 28,000 men which included Korean laborers who were used for building military emplacements.

The Marshalls were the next obvious target after the Gilbetrs were secured. There was nothing of great importance on the ilands, they were just a barrier to the western movement of American power to first sever the Home Islands from the resources seized in Southeast Asia and then north toward the Home Islands. American planners debated how to assault the Marshalls. The JCS War Plans Committee recommended attacks on several islands, begining with Wotje and Maloelap at the northern fringe of the the Marshalls. The feeling that these islands would provide the logistical bases and air platforms for further strikes on other important islands. This was the general consensus that emerged from staff studies and duiscussions. Rear Adm. Turner, commander of the Fifth Amphibious Force, Marine Corps Maj. Gen. . Smith, commander of the V Amphibious Corps, and Vice Adm. Raymond A. Spruance, the Fifth Fleet commander all councurred with the Joint Chiefs. It was not yet widely understood that destroying Japanese aircraft on these islands and denying them supplies would render them impotent. Admiral Nimitz understood this as well as the fact that every island invasion would result in an increasing tool of American casualties. Nimitz argued thst the United States should focus the attack on Kwajalein and simply bypass most of the other islands. Nimitz wanted to hit the smaller islands with naval gunfire and air strikes, but only invade Kwajalein even though it was located in the center of the Marshalls. Wotje and Maloelap

could support Kwajalein, but only if their airfields and air component was still in tact. Nimitz thus planned to begin the opertion with simultaneous air attacks on Kwajalein, Wotje, and Maloelap. This would neutralize more than 65 percent of the enemy aircraft in one bold stroke. And the new Essex-class carriers and Gruman F6F Hellcats reaching the fleet gave Spruance and Nimitz the capability of doing just this. Nimitz argued that his strike at the heart of Japanese power in the Marshalls is not what the Japanese would be expecting. The Japanese would be surprised and unprepared for it. One in American hands, air strikes from Kwajalein could complete the neutralization of the outer islands. Nimitz saw this as perhsps the central lesson of Tarawa.

American code breakers had broken the Japanese purple diplomatic code a year before Pearl Harbor (1940). The Americans called it Magic at first. The naval code (JN-25) proved more difficult, but was penetrated suffiently to provide advanced warning of the Japanese Coral Sea and Midway plans (1942). These break throughs were made with still small staffs and limited resources. After Pearl Harbor, enormous resources were thrown at code breaking. After Midway, the American effort merged with the British Ultra effort. The British focused primarily on the German Enigma machine. The Americans were able to devote greatly expanded resources and thus expanded their work on Japanese codes to include German codes as well. Not only was JN-25 and subsequent codes penetrated, but the Japanese Army code was also broken (early 1943). And they were not brokn partially, but throughly. As the War progressed, the Americans steadily increased their interception and decodeing capability. One of the unanswered questioins of the War is why both the Japanese and Germans refused to believe that their codes were broken inspite of clear evidence to the contrary. The Americans were reading Japanese messages often before the recipients were able to receive and decode them. Thus the Americans had information on Japanese deploument and force structure in great detail. Nimitz has access to this, but not his subordinates. We are not entirely sure how much Spuance knew. And Ultra reports informed Spruance that the Japanese expdecting the Americans to attack the outer islands, had shifted a substabtial part of their forces there instead of concentrating on Kwajalein. This by avoiding the outer ialands and invading Kwajalein, Nimitz was able to avoid the bulk of the Japanese force and attack a poorly defended island. And without air and naval assetts, the bypassed the outer islands were essentially out of the War. In fct by the end of the War, the garrisons on these islands were at the point of starvation.

The Marshalls campaign actually began as part if the Gilberts Cmpaign. Mille Atoll in the eastern Marshalls was within Japanese fighter range of the Gilberts. Thus Admiral Nimitz approved an attack on Mille before the U.S. Army and Marine Corps landed on Makin and Tarawa. An American air strike devestated the Japanese air forces on Mille (November 20, 1943). Japanese forces lost 71 air craft. The Japanese were able to replace the losses, primarily by moving aircraft forward from Truk or shipments from Japan. Further reenforcements became increasingly difficult. Next the Americans hit Taroa airfield on Maloelap (November 26). The Japanese continued to use it until further air attacks put it permanentlyh out of commission (January 29, 1944). Next the Japanese airfields on Jaluit and Wotje were attacked (early January). At this time major air raids on Kwajalein began. And as the time table for Flintlock approched, the Americans stepped up the air strikes. The Japanese still had 110 operational aircraft in the Marshalls (January 25), days before Flintlock. Ultra decrypts had, however, revealed their precise location. In a final pre-invasion strilke, American avitors destroyed or damaged 92 Jpanese aircraft on Roi-Namur-on the northeast quadrant of the Kwajaleion atoll. This left only 15 operatrional planes, giving the Americans air superiority. Japanese air power in the eastern Marshalls essenially no longer existed.

The invasion plan involved the 4th Marine Division to seize Roi-Namur and other islands in the northeast quadrant of the atoll. The Army 7th Infantry Division was to seize the island of Kwajalein which was located 44 nautical miles south of Roi-Namur in the extreme southeast of the atoll. Separate from the Kwajalein invasion, the 2d Battalion of the 106th Infantry was ordered to seize on the eastern fringe of the Marshalls. Admiral Spruance wanted Majuro as a fleet ancorage and airfield for further operations.

The island of Kwajalein is two and one-half miles long and 800 yards wide for most of its length, tapering to 300 yards wide at its northern end. The seaward side had long been fortified, but since the enemy had also been erecting defenses on the lagoon side, General Corlett decided to avoid a frontal assault. His 7th Infantry Division was to come ashore on the western end of the island, which had a beach 400 yards deep, and attack with two regiments abreast. On 31 January, the day before the assault, his forces were also scheduled to seize four small islands surrounding Kwajalein to serve as artillery bases and to ensure unimpeded access to the lagoon. General Schmidt's plan for capturing Roi-Namur was similar. His forces would seize five islands surrounding his main objective on 31 January and conduct their primary landing on 1 February.

The Kwajalein invasion was at first set for (January 17). Supply problems and training needs forced a postponment.

The Japanese because of the air attacks had expected an American invasion force to appear imminently at the outer Marshalls. They were surprisded with the Americans appeared off Kwajalein. As the air defenes had been obliterated, the outer islands could not impede the passage of the American fleet or support the forces on Kwajalein. Unlike Tarawa or the outer islands, relatively little work was done on Kwajelin preparing the island for an American assault. An what work that was done was to defend against a landing on the seaward side of the island rather than the lagoon side. Intelligence reports from Tokyo described the capabilities of Amnerican landing vehicle-tracked (LVTs). The landing vehicles were capable of climbing over coral reefs. As a result, the Japanese began constructing defensive positions on the lagoon side of many islands. Littletimecwas left and at any rate anin-depth defense of the island was impossible because it was so narrow. The same proved true of other atolls. American naval gunfire and air assaults began (January 28). The Americans raked Kwajalein for 3 days with far greater accuracy than in the Gilberts. Frogmen blew holes in the reef at key locations. The Marines landed (January 31). Artillery was set up on offshore islands. Kwajalein was taken in 4 days with less than 2,000 casualties, a fraction of the horific Tarawa landings.

The smaller islands were subjected to air attacks and naval gunfire rendering them impotent.

This success and the lack of any indication that the Imperial Fleet would intervene caused Nimitz to move up the assault on Eniwetok from May 1 to February 17. Forces were available because Kwajalein proved less costly than abticipated and the other islands had been bipassed. Eniwetok was 1,000 miles further west, but as dexpected the Imperial Fleet did not intervene. The Americans landed 8,000 men, two reinforced regiments (February 17). They were opposed by 2,000 Japanrse. Mistakes were made, especially with the naval gunfire. The Japoanese resisted tenaciously, almost to a man. But the island was in American hands (February 22). The cost was less than expected--about 1,000 casualties including 300 killed.

Navigate the Boys' Historical Clothing Web Site:

[Return to Main World War II Marshall Islands page ]

[Return to Main World War II Marianas page ]

[Return to Main World War II island territory page ]

[Return to Main World War II country page ]

[Return to Main Marianasa history page]

[Introduction]

[Activities]

[Biographies]

[Chronology]

[Clothing styles]

[Countries]

[Bibliographies]

[Contributions]

[FAQs]

[Glossaries]

[Images]

[Links]

[Registration]

[Tools]

[Boys' Clothing Home]