World War II: Japanese Surrender -- The Emperor's Speech (August 14, 1945)

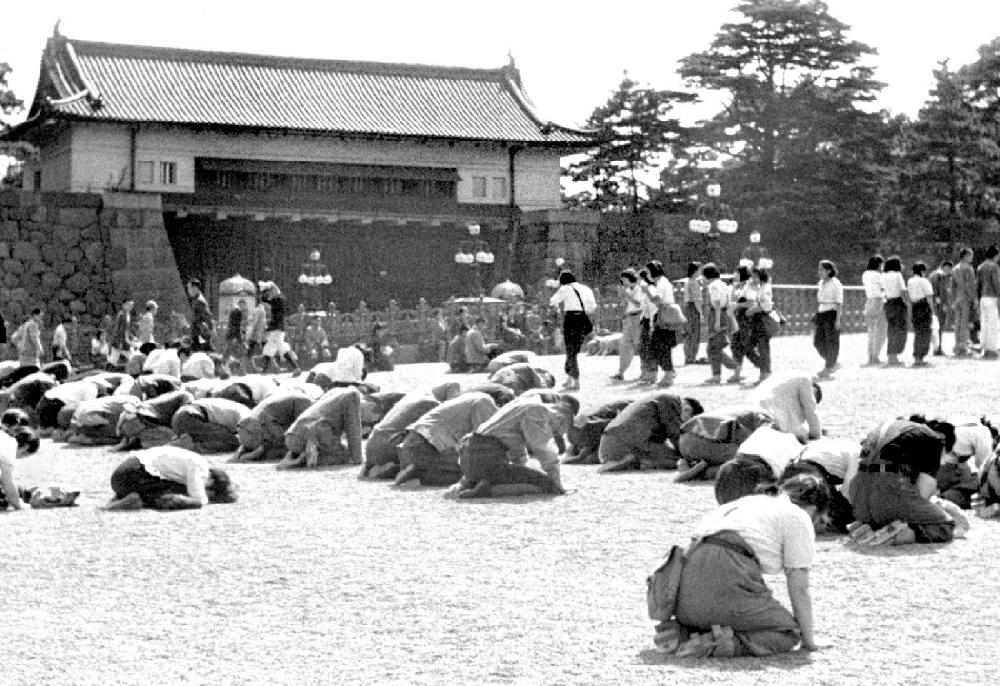

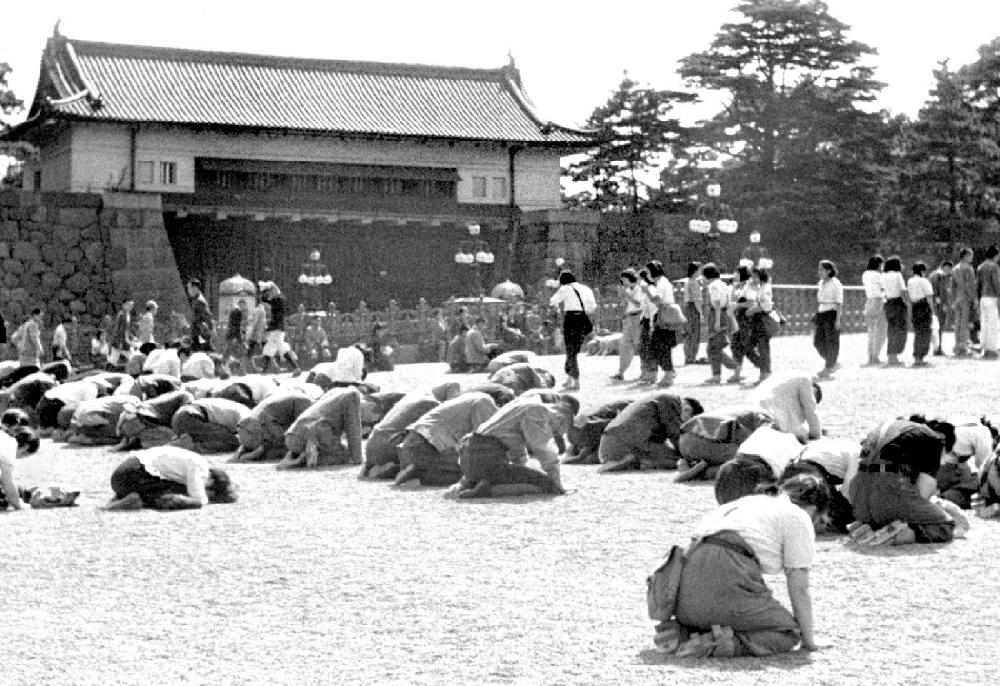

Figure 1.--The Emperor's announcement was broadcast to a stunned nation (August 14). It is difficult for us today to understand the depth of veneration in which the Japanese pdople and military held the Emperor. Venerating him as a god seems so arcane to us today. But much of the Japanese people believed just--although the concept od divinity was different than that if the Abrahamic religions (Christianity, Islam, and Judaism). Even so the depth of this feeling was a major factor in the very real and continuing Japanese determination to resist to the end. Photographs of the public listening to the speech (many Japanese did not have home radios) give an idea of the reverence in which the Emperor was held.

|

|

"Despite the best that has been done by everyone--the gallant fighting of our

military and naval forces, the diligence and assiduity of out servants of the State and the devoted service of our 100,000,000 people--the war situation has developed not necessarily to Japan's advantage, while the general trends of the world have all turned against her interest. Moreover, the enemy has begun to employ a new and most cruel bomb, the power of which to do damage is, indeed, incalculable, taking the toll of many innocent lives. Should we continue to fight, it would not only result in an ultimate collapse and obliteration of the Japanese nation, but also it would lead to the total extinction of human civilization." Emperor Horohito, August 14, 1945.

The Emperor's announcement was broadcast to a stunned nation (August 14). It is difficult for us today to understand the depth of veneration in which the Japanese pdople and military held the Emperor. Venerating him as a god seems so arcane to us today. But much of the Japanese people believed just--although the concept od divinity was different than that if the Abrahamic religions (Christianity, Islam, and Judaism). Even so the depth of this feeling was a major factor in the very real and continuing Japanese determination to resist to the end. Photographs of the public listening to the speech (many Japanese did not have home radios) give an idea of the reverence in which the Emperor was held (figure 1). The broadcast was a mixture of understatement and outright falsehood. He began, "To our good and loyal subjects: After pondering deeply the general trends of the world and the actual conditions obtaining in our empire today, we have decided to effect a settlement of the present situation by resorting to an extraordinary measure. We have ordered our Government to communicate to the Governments of the United States, Great Britain, China and the Soviet Union that our Empire accepts the provisions of their joint declaration. To strive for the common prosperity and happiness of all nations as well as the security and well-being of our subjects is the solemn obligation which has been handed down by our

imperial ancestors and which we lay close to the heart. Indeed, we declared war on America and Britain out of our sincere desire to insure Japan's self-preservation and the stabilization of East Asia, it being far from our thought either to infringe upon the sovereignty of other nations or to embark upon territorial aggrandizement. But now the war has lasted for nearly four years. Despite the best that has been done by everyone--the gallant fighting of our military and naval forces, the diligence and assiduity of out servants of the State and the devoted service of our 100,000,000 people--the war situation has developed not necessarily to Japan's advantage, while the general trends of the world have all turned against her interest. Moreover, the enemy has begun to employ a new and most cruel bomb, the power of which to do damage is, indeed, incalculable, taking the toll of many innocent lives. Should we continue to fight, it would not only result in an ultimate collapse and obliteration of the Japanese nation, but also it would lead to the total extinction of human civilization. ...." The Emperor never used the

term 'surrender', but it was a surrender and ended the Pacific War. It was the first time the Japanese people had heard the Emperor's voice.

Public Broadcast

Photographs of the public listening to the speech (many Japanese did not have home radios) give an idea of the reverence in which the Emperor was held (figure 1).

The Text

At 12:00 noon Japan standard time on August 15, the Emperor's recorded speech to the nation, reading the Imperial Rescript on the Termination of the War, was broadcast. It was a mixture of understatement and outright falsehood. He text reads, "To our good and loyal subjects: After pondering deeply the general trends of the world and the actual conditions obtaining in our Empire today, we have decided to effect a settlement of the present situation by resorting to an extraordinary measure. We have ordered our Government to communicate to the Governments of the United States, Great Britain, China and the Soviet Union that our Empire accepts the provisions of their joint declaration. To strive for the common prosperity and happiness of all nations as well as the security and well-being of our subjects is the solemn obligation which has been handed down by our

imperial ancestors and which we lay close to the heart. Indeed, we declared war on America and Britain out of our sincere desire to insure Japan's self-preservation and the stabilization of East Asia, it being far from our thought either to infringe upon the sovereignty of other nations or to embark upon territorial aggrandizement. But now the war has lasted for nearly four years. Despite the best that has been done by everyone--the gallant fighting of our military and naval forces, the diligence and assiduity of out servants of the State and the devoted service of our 100,000,000 people--the war situation has developed not necessarily to Japan's advantage, while the general trends of the world have all turned against her interest. Moreover, the enemy has begun to employ a new and most cruel bomb, the power of which to do damage is, indeed, incalculable, taking the toll of many innocent lives. Should we continue to fight, it would not only result in an ultimate collapse and obliteration of the Japanese nation, but also it would lead to the total extinction of human civilization. ...."

Surrender

The Emperor never used the

term 'surrender', but it was a surrender and ended the Pacific War. It was the first time the Japanese people had heard the Emperor's voice.

The Emperor's announcement legally took the form of a Rescript. This is an edict, an official order or proclamation issued by a person in authority. It is normally associated with a monarchial system like the Japanese Empire. Major policy decesions after the Meiji Restoration (1860s had come as Imperial Rescript, none had been delivered as a broadcast. The broadcast stunned a nation thathad been repearedly told that they were winning the war (August 14). Of course the battles colser anbd closer to Japan and the American bombing must have shown the populatin that the War had gine very badly. The Japanese people had never heard the Emperor's voice before. That alone priobably disorienrd and stunned much of the nation. The Emperor did not speak live to he nation like Churchill and Roosevelt with their resonn voices. He had previously recorded the message. One report indicates that the quality of the recording was poor. And this combined with the classical Japanese language used by the Emperor meant that many of his subjects did not fully understand what they were hearing. It is difficult for us today to understand the depth of veneration in which the Japanese people and military held the Emperor. Venerating him as a god seems so arcane to us today. But much of the Japanese people believed just--although the concept of divinity was different than that of the Western Abrahamic religions (Christianity, Islam, and Judaism). Even so the depth of this feeling was a major factor in the very real and continuing Japanese determination to resist to the end. Japanese soldiers simply refused to surrender. And many of those soldiers where there were Japananese civilians expecred the them to do the same (Saipan and Okinawa). The Emperor's Rescript ended that meaning that this tragedy would not occur on the Home Islands. Few civilians were fully aware at the time of the full dimensiions of the tragedy that might have unfolded or what the Emperor had prevented. Reports suggest that the public reaction to the Emperor's speech varied. Many Japanese reportedly listened and then went on with their daily lives. Quite a number of senior Army and Navy officers chose suicide, but not as many as one might expect given that theyb ordered so many young men to fight to the death even aftr battles had been lost and isolated garrisons were essentially ordered to starve to death rather han surrender. Former prime-minister Tojo shot himself, but botched the job. One historian reoorts that a small crowd gathered in front of the Imperial Palace in Tokyo and cried. The tears they shed "reflected a multitude of sentiments ... anguish, regret, bereavement and anger at having been deceived, sudden emptiness and loss of purpose". [Dower, p. 38-39.]

Two Week Hiatus (August 14-September 2)

There was slightly more than a two week hiatus between the Emperor's announcement (August 14) and the formal surrender on the battleship USS Missouri (September 2). The situation in Japan was very different than in Germany after the NAZI surrender. At the time of the NAZI surrender, much of the Reich had been occuopied by Allied and Soviet forces. All of the Home Islands were still in Japanese hands. This enabled the Imperial Goivernment and military to conduct destruiction of documments on a vast scale. The Japanese did not keep as careful records as the Japanese. And it meant whenthe Americans arrived many ministries and the military had virtully no records to sort thriugh, not to mention the fact, that unlike Germany, the Americans had vert few Japanese speakers working with the occupation. The result was that the IMP investigators unlike their counterparts in occupied Germany did not have mounds of documentary evidence. Apart from doument destruction, the most immediate problem was the still functiining foield armies in the Duth East Indies, Singapore, Malaya, and large areas China. The starving Japanese island garrisons were amenable to surrender. Many of the commanders in the other field armies were stunned at the surrender broadcast and not at all disposed to surrender. Commanders in China had an especially difficult problem. They had muurdered all the Chinese prisoners they had taken during 8 years of war. There were no POWs to release. Not to mntion the vast number of civilians murdered. Given that enirmous war crime, surendering to the Chinese was nt an ebviable proposition. A major effot was made to gain compliance. The Japanese armies in Manchuria were being overun by the Soviet offensive. The Imperial Goverment decided to resist militarily any effort by the Soviets to take the Kuril Islands. Here the Soviets had difficulty because of the lack of any amphibious capability.

After nearly 4 years of implacable combat, The Japanese Imperial Government formally surrendered to the Allies on the morning of September 2, 1945. This was more that 2 weeks after accepting the Allies terms. This interval gave the Japanese two weeks to destroy mountains of incriminating documents. And every ministry wnt after this task with a vengence. As a result, the Tokyo IMT War Ceimws trial lacked the massive documntary record of the Nuremberg trials. The ceremonies overseen by General MacArthur who insisted on this rather than Admiral Nimitz. The ceremonies were finally conducted aboard the battleship USS Missouri, anchored in Tokyo Bay. The Missouri was anchored along other American and British ships. The ceremony took less than half an hour. Japanese officials signed the instruments of surrender under the Missouri's big guns. Allied supreme commander General Douglas MacArthur sined for the Allies. Japanese foreign minister, Mamoru Shigemitsu, and the chief of staff of the Japanese army, Yoshijiro Umezu, signed fot the Japanese. This effectively ended the Pacific War. The ceremony was carefully staged by General MacArthur. Not knowing just what the Japanese were planning, the American carriers were standing on station out to sea off Japan and massed squadorns of aircraft overflew the ceremony. American troops landed in Japan immediately after the Imperial Government surrendered. Manyhaving experienced fanatical Japanese resistance on Pacific island battlefields, were unsure what to expect. As it tyrned out, the Japanese peopleand military docily accepted occupation. This was the price the allies paid for not procecuting the emperor as a war criminal.

Sources

Dower, John (1999). Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II (W.W. Norton: 1999).

CIH -- WW II

Navigate the CIH World War II Pages:

[Return to Main World War II Pacific campaign: Atomic bomb page]

[Return to Main Presiden Truman's decision page]

[Return to Main Japanese World War II surrender page]

[Return to Main Japanese World War II page]

[Return to Main World War II Pacific campaign page]

[Return to Main Axis surrender page]

[About Us]

[Biographies]

[Campaigns]

[Children]

[Countries]

[Deciding factors]

[Diplomacy]

[Geo-political crisis]

[Economics]

[Home front]

[Intelligence]

[Resistance]

[Race]

[Refugees]

[Technology]

[Bibliographies]

[Contributions]

[FAQs]

[Images]

[Links]

[Registration]

[Tools]

[Return to Main World War II page]

[Return to Main war essay page]

Created: 5:27 PM 8/21/2016

Last updated: 7:56 AM 7/14/2018