Boys' Hair Styles: The 18th Century

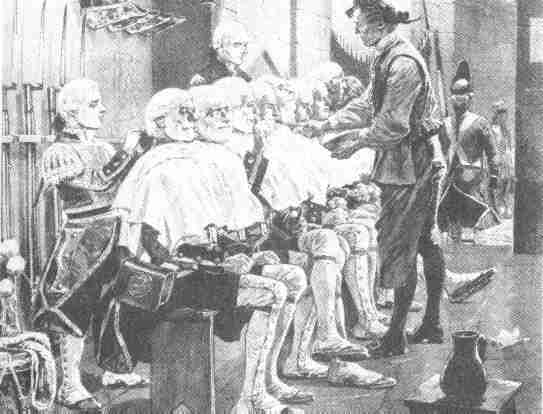

Figure 1.--This 18th century drawing shows British soldiers undergoing wig dressing in preparation for guard duty. They were shaved and had their wigs powdered in one setting. Notice the drummer boy, also wearing a wig, tieing the ribbons to their queues.

|

No well-dressed gentleman in the 18th century would have thought himself completely dressed without a wig. Many men had several wigs of different styles. There was a wide range of styles, but two basic types those worn with or without queues (pigtails). The queues were secired with ribbon bows. While wigs were primarily worn by adults, boys from affluent families might also wear a wig.

Womens' Hair Styles

Early 18th century

Women in the last two-thirds of the 17th and the early 18th century wore generally simple hair styles.

Mid-18th century

Toward the middle of the 18th century, feminine coiffures in France became increasingly complex. This was imprtant as fashionable women throughout Europe, including England, followed French styles. During the reign of Louis XV, French women were wearing lofty constructions of curls stiffined with wire, cloth, or other materials. One of Louis XV's mistresses, Madame de Pompadour, played an important role in popularizing new elaborate hair styles. She had countless different styles and cortisons at the court had trouble keeping up with her. On top of the huge ediface of hair was placed a cap or hat decorated with flowers or plumes. It was Madame Pompedour that gave womwn's hair one of its most common modern features--wearing it without a part. She combed her hair straight back from rgw firehead and worn high at the front. [Bill Severn, Hair: The Long and Short of It (David McKay: New York, 1971), p. 67.]

In the reign of Louis XVI the style became even more extravagent. Soon women were wearing huge constructions on their hard supported with wire and other materials. Everyone competed with each other for the more ellaborate, complicated constructions. Natural hair arranged on wire was stuffed with cotton, wool, rope, horsehair, bran, straw, and other materials. Victorious naval battles were even celebrated in women's hair dos. The extreme was perhaps reached by a hairdresser of the 18th century was devised the coiffure à la frégate, a high vertical structure of hair held in place by gigantic combs and adorned with jewels, the whole crowned by the model of a period war ship. Greasy hair stuffed with materials likely to rot, especially during the summer, created a strong market for perfumers. The frivolus Queen Marie-Antoinette promoted the use of ostrich feathers which added even more height to hairdos. The style spread to England and the opponents of long mens' hair for a time directed their moral tirades at womens' hair styles.

Mens' Hair Styles

The story of men's hair fashions in the 18th century is largely an account of wigs. Men in the 18th century continued to wear wigs, in fact wigs became even more common in the 18th century. This was in part a reflection of increasing prosperity in Europe. More men could now afford them and not just wealthy arristocrats. Fashion arbiteurs advised that wigs were "... as essential to every person's head as lace is to their clothes". [London Chronicle, 1726] The editorial, however, wentvon to complain that the new rage for wigs made many men look like the rows of pots displayed on drug store shelves "which are much ornamented but always stand empty". Wigs were worn in many different styles. Nen wore their hair in a different variety of styles then ever before. Many men had wigs of differing styles, limited only by their pocket book. Satrist Peter Pindar wrote:

Those wigs, which once were worn alone by kings,

Whence they derived their air of awful state,

Now decorated every plebeian pate ...

Wig styles

While wigs became even more common in the 18th century, several major changed occurred in hair and wig styling. Some of the changes included:

Size: The massive wigs of the 17th century declined in popularity although they comtinued to be worn by older gentlemen in some professions. They are still worn, for example by English judges.

Color: More and more men wore powdered white wigs rather than the dark colored wigs of the 17th century.

Pig tails: Pigtails were intereyingly not only initially a male hair style, but a military style. This might come as a surprise to little 20th century boys who delighted in pulling little girls' piftails. Pigtails or queues were, in fact, the most obvious difference between 17th and 18th century wigs and hair styles. The style was apparently born in the military. Soldiers and sailors in the wars of thecearly 17th century began combing their hair to the back out ot of the way. The curls were bunched together and held their with a ribbon. The pigtails were sometimes braided or stiffened with pipe clay or even tar. Military wigs appeared with detachable pigtails, some of hairm but others of wood, baleen, leather, or wire with tufts of hair at the end.

Ribbons and bows: Soldiers began adding ribbons, sometimes tied in discrete bows to secure their pigtails.

Many different styles of wigs were worn in the 18th century. Some of the different styles included: short bobs, long bobs, tie wigs, bag wigs, tick up wigs, naturals, half naturals and many others with more artistic names like "Grecian flyers," "Curley Roys," and "Airy Levants". Basically, however, there were two general styles, those with or without queues (pig tails). Each styles had its proponents and critics.

The wig industry

Any large city would have hundreds of wig makers. A small toun of any size would commonly have at least two. The wigs in these shops hung in rows on stands topped by wodden heads. The craft of wig making bcame an art that produced detailed books of instruction and styling. Wigs were curled over hot clay pipes and doctored with special tools. They were cairred in boxes specially designed to preserve their form. Advertising had become more common in the 18th century. One London wig maker offerred wigs that gave the clergyman "a certain demure, sanctified air," lawyers "an appearance of great sagacity and deep penetration," professional men "solemnity and gravity," and the military "a most warlike fierceness". [Bill Severn, Hair: The Long and Short of It (David McKay: New York, 1971), p. 39.]

Powdering

One aspect of waring a wig for most of the century was powdering it. Powdering the wigs was considered essential. Soldiers did it in their barracks. The wealthy buits rooms just for powdering, the original powder rooms. The less affluent had to do it in their attic or a barbershop. When having his wig powdered, the individual wore his wig smeared with grease. He would wrap himself in a cloth or robe covering the entire body except for the head. Often the individual would bury his face in a face shield made of paper or glass. The powder was then dumped on his head or pumped from a hand bellows. The wealthy used scented powders, usually white, although some dandies preferred blue or violet. The less afluent might use plain flour. Men who over powdered his wigs left trails of it in the air when they walked.

Cost

Wigs were very expensive. A man could reportedly buy a complete outfit, hat, coat, shirt, breeches, and shoes for the cost of a good wig. And it was not just the initial purchase price that was involved. Dressing and caring for wigs was also a significnt expenditure. Often men paid their barbers an annual fee for shaving and wig dressing.

Country patterns

Wig wearing patterns in Europe were quite similar, this was in part due the extent to which to which styles were influenced by the elegant French court.

Europe: Most European nobels and gentlemen wore wigs. Wig wearing was almost universal in cities, except for the very poor who could not afford them.

America: Wig wearing was also common in America. They were worn by college teachers and students, magistrates, preachers--even low paid ones, craftsmen and their aprentices, and even house slaves in the South who might wear white goat's hair wigs. Wigs were much less common in rural areas, especially pooer and frontier areas. Reports from colonial America indicate city dwealers traveling in rural and being shocked by seeing so many men without wigs. America was laregely rural at the time of the Revolution (1776-83). Americans varied. Some wouls not be caught with out a wig. Adams wore a formal powered wig as Ambassador to France during the Revolution. He disliked and was glad to discard it when he returned to America, but often felt compeled to wear it as Vice President. Jeffereson varied through his life. Washington rarwly wore a wug, preferring his own hair. During the Revolutiin, However, he wore his natural hair powdered and often with a queue which he tied with a ribbon or cobered with a black bag. Many of his Continental soldiers and militia wore their own natural long hair. Reportedly the militia that was raised in Virginia frightened the citizens of Williamsburg, at the time the capital. Their long natural hair was in many cases worn untied without queues and they thus looked to the townspeople like savages. Wig wearing was more common in New England, but often mobs amused themselves by ripping the fancy wigs off Torries and micking them. James Murray, a Bostobn Torry, described how a crows "made sport" of him by holding his arms and pulling off his wig. They made him parade home with his "pate ... left exposed" while a jeering mob followed with his "wig dishevelled ... born on a staff behind." The Revolution turned many against wigs, but the fashion persisted for some time. Many who signed the Declatation of Independence wore wigs. It was not until wig wearing in Europe declined after the French Revolution that wig wearing ended in America--Americans still following European fashion trends.

Changing fashion

Wigs were worn most of the century, but by about 1765 some young men had begun to wear their natural hair rather than wigs. Most continued wearing wigs until the French Revolution (1789) began to affect fashion. Some even took to wearing elaborate wigs, forming the Macaroni Club. They adopted many extreme fashions. They were the inspiration for the Yankee Doodle Dandy, who as we know "stuck a feather in his cap and called it macraroni".

Figure 2.--John Randolph of Virginia is shown here at about 14 years of age. That would have mean about 1787. He wears his hair cut short and swept forward in a style harkening back to Rome.

|

Childrens' Hair Fashions

While wigs were primarily worn by adults, boys did also wear wigs on occassion. There was probably a class element involved because of the cost. Boys from affluent families were probably more likely to wear wigs. One source suggests that boys began wearing wigs at about 7 years of age, but I so little information on this that I can not confirm that this was a widely followed convention for boys. Boys appear to have worn the same style of wigs worn by thier fathers, al least after breeching. I know of no special boys' wig style. For this reason HBC has covered mens' wig styles in such detail. Little information is available on boys' wigs and boys wore the same styles as adults. Both boys and men, for example, wore ribbon bows to secure their queues.

HBC believes that wig wearing by boys began to decline significantly after the mid-17tyh century, before the trend became popular for men. While a young boy might wear a wig for a formal occassion, most boys did no wear them. Most of the portraits I have seen show boys without wigs. Many boys, however, did wear queues, but usually not powdered. This began to change by the 1780s, even before the French Revolution, when short hair became increasingly common for boys.

I have little information on childrens' wig wearing. Several questions arise. To what extent did boys wear wigs? When did they start? Did boys wear girls' wigs before they were breeched? Did boys always adopt the style of wig worn by his father?

Christopher Wagner

histclo@lycosmail.com

Navigate the Boys' Historical Clothing Web Site:

[Return to the Main European hair style history page]

[Introduction]

[Activities]

[Bibliographies]

[Biographies]

[Chronology]

[Clothing styles]

[Contributions]

[Countries]

[FAQs]

[Literary]

[Boys' Clothing Home]

Created: March 9, 2000

Last updated: March 13, 2000