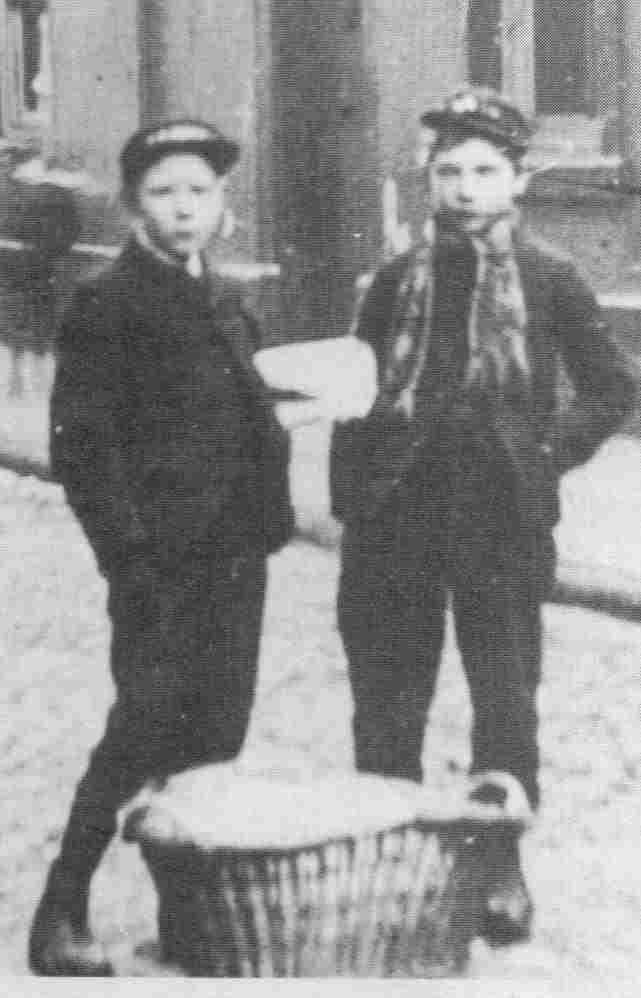

Figure 1.--These boys are working as errand boys in Lancaster sometime about the turn of the 20th century. |

|

Children in the 18 and 19th children were involved throught the British economy, including many of the most important industries. They along with women were employed in both mines and. Often they were given some of the most dangerous jobs. The age of the boys depended on the size of the mineshafts: wide ones enabled boys aged 14–18 to work but thinner ones necessitated using boys as young as 7 until the 1842 Mines and Collieries Act banned the use of boys aged under 10 below ground. In the cotton industry, adult workers were paid on a piece-basis i.e. according to the amount they produced. A system of sub-contracting existed which meant that many child workers, instead of being directly employed by the manufacturer, were employed by adults and paid out of their wages. In the 1830s the use of 3 children per spinner had become the norm. Typical tasks were: “Scavening” - Children oiled the machinery and wiped down twice daily as the machines powered down for the midday break and evening closedown. Hawkers sold anything from matches and ice creams to flowers and hot peas. Some were knife sharpeners, others organ grinders. One regular job was as a “knocker-up” i.e. to walk along the street, early in the morning, carrying a long stick with which to hit the bedroom windows to wake people up in time for work. The most common street trade was selling newspapers. The clerk and Post Office telegraph boy appeared to be promised job security and many parents considered them as being in respectable employment. Unfortunately clerks were little more than messenger boys and cleaners; furthermore they usually earned less than mill operatives did. Shop boys were used to mind pavement displays from being stolen or act as door-boys for high-class stores. Some even served the customers. At seaside resorts boys made ice creams or carried bags for tourists at railway stations. Local children played truant from school to work for the summer, usually with their parents’ permission, because they had to compete with migrant boys from the cities also looking for work. Usual tasks were scaring off birds, tending animals, driving the plough and assisting the “carter” or cowman. Small farms employed very few servants and only a limited seasonal agricultural labour when necessary.

Mining has been carried on in England since the Bronze age. Somerset was an important source of tin during the Bronze Age. We have no idea about mining during ancient times or evem the medieval era. More information is available with the onset of the Industrial Revolution. Mining becme inportant as a source of both coal and iron ore. Women and children were among those employed in mines during the 18th century. We do not know what portion of the mining work force they represent. Miners are generally seen as big burly men and nost were. Many mining jobs required strong powefully built men. But there were many mining jobs that did not require braun and other where small-sized individuals were useful. This was especially true in early mines. In the 19th century laws were passed which banned cthe use of women and younger bots. Many teenagers worked in the mines through the late-129th and early-20th century. Boys usually started as door-tenders or trappers until they graduated to other jobs. They opened air-doors to make way for wagons and closing them again once they had passed. It was a lonely existence being on your own in the dark for 12 hours per day, waiting to open the door when requested. “Wagoners” pulled or pushed trucks filled with coal whilst “Giggers” applied the wagon’s brakes. “Drawers” dragged coal underground in baskets from the coalface to the shafts. Because colliers were paid on the basis of the quantity of coal delivered from the coal face to the shaft they tended to employ their own sons to act as “drawers” and thereby keep the entirety of their wages in their own families. The age of the boys depended on the size of the mineshafts: wide ones enabled boys aged 14–18 to work but thinner ones necessitated using boys as young as 7 until the 1842 Mines and Collieries Act banned the use of boys aged under 10 below ground.

In the cotton industry, adult workers were paid on a piece-basis i.e. according to the amount they produced. A system of sub-contracting existed which meant that many child workers, instead of being directly employed by the manufacturer, were employed by adults and paid out of their wages. In the 1830s the use of 3 children per spinner had become the norm. Typical tasks were: “Scavening” - Children oiled the machinery and wiped down twice daily as the machines powered down for the midday break and evening closedown. Any oil was carefully wiped away, along with cotton waste or fluff. This “scavening” process was expressly forbidden, from 1878, to be carried out whilst the machinery was in motion. Photograph Number 6 Dennis, shows a boy on the right “scavening” under the working machinery in 1835 and therefore predates the ban on such an activity. “Carding” – this process prepared the cotton wool for spinning and it employed a machine that laid cotton fibres flat and parallel by means of hundreds of tiny metal barbs, producing a “card-web” – an almost transparent film of fibres. Renewal of the metal cans receiving the resulting “slivers” or thick, loose ropes of cotton was undertaken about every 15 minutes by children. The tiny metal bars used by this equipment were also replaced as necessary and a hand inserted too far into the machine could result in the loss of fingertips. Copious quantities of dust were thrown out, liable to be breathed in. Photograph Number 7 Dennis, shows carding machinery. Note the small boy working on the middle one. Photograph Number 8 Dennis, shows another part of the “carding” process in action. “Piecing” involved the repair of threads broken during the mule-spinning process. Young children carried out this process particularly during a “sawney” i.e. a simultaneous breakage of every thread in the mule. Photograph Number 9 Dennis, shows a piecer sweeping up in 1900. Note he is barefoot to help grip on the oil-covered floor. One boy who later qualified as a school teacher recalled his childhood work “I performed it, unresting, in my bare feet. Sometimes splinters as keen as daggers drove through my naked feet leaving aching wounds from which dribbles of blood oozed forth to add to the slipperiness of the floor. I just had to try to avoid the splinters and the falls; there were few chances to tear the jagged bits of wood away while those unprotected machines were on the move. My ten-year-old legs felt like lead and my head spun faster than the pitiless machinery. But I had to keep on; the dinner whistle would shrill some time soon; then I could rest and regain my breath, ready to run two miles home to dinner, and then set off for school.”

Hawkers sold anything from matches and ice creams to flowers and hot peas. Some were knife sharpeners, others organ grinders. One regular job was as a “knocker-up” i.e. to walk along the street, early in the morning, carrying a long stick with which to hit the bedroom windows to wake people up in time for work. The 1903 Employment of Children Act prohibited all those under 11 years from any selling and those under 14 from trading before 6.00 a.m. or after 9.00 p.m. However these laws were only partially effective because parents paid little attention to them due to the need for children of the poor to help the family economy where regular adult employment was scarce. Therefore children either traded without a licence or misrepresented their age to make sure they obtained a trading licence. It was not unknown for magistrates to deal leniently with those who broke the trading licence laws because it was felt that many boys had difficult conditions to contend with at home.

The most common street trade was selling newspapers. It must have been especially difficult to enforce the street trading regulations on news boys. We note large number of photographs of boys selling newspapers.

Shop boys were used to mind pavement displays from being stolen or act as door-boys for high-class stores. Some even served the customers. Note the large aprons to protect their clothing from the produce.

Errand boys made home deliveries of goods such as milk and bread when shops increased their services to compete with each other. Van boys or “nippers”, would accompany the driver to guard the van from theft, look after the horse or assist the driver in the delivery of parcels. “Nippers” “retired” at age 17 because businesses were incapable or paying for them as “adult workers”. It was only when they reached the age of 21 could they be considered as “carters” or “carmen”. Consequently there were two major concerns for those entering shop trades after leaving school: The first was the physical aspect of working long hours and carrying heavy loads. Full-time shop hours were 84 hours per week; this compared unfavourably with 60 hours per week in factories. Boys went into the shop early to set up and stayed late to clear up; many also worked the Saturday afternoon, which was a half-day holiday for adults. The 1888 Shops Act limited the hours of children working there to 74 hours per week.

The second was the poor promotion prospects or possibility of moving into skilled employment. Boys only took up shop employment for the short period after leaving school before they were able to enter a trade, but it still did not lead onto a future career because there was no chance of acquiring knowledge about the products they were selling or distributing.

The clerk and Post Office telegraph boy appeared to be promised job security and many parents considered them as being in respectable employment. Unfortunately clerks were little more than messenger boys and cleaners; furthermore they usually earned less than mill operatives did. As for promotion to becoming adult clerks, many found that the basic reading, writing and arithmetic skills they acquired at school were not sufficient to handle office style accounts. Telegraph boys or boy messengers were given the impression of permanence because the Post Office, being a government department, offered good prospects. The impression of permanence was heightened by the apparent care which was shown in the selection of messengers; they had to be of a certain height, produce testimonials to their character, furnish a copy of their birth certificate and be medically sound and “vaccinated”. In truth only a small number were absorbed into the adult service.

At seaside resorts boys made ice creams or carried bags for tourists at railway stations. Local children played truant from school to work for the summer, usually with their parents’ permission, because they had to compete with migrant boys from the cities also looking for work. Cockle-picking in Morecambe harbour was also a popular work experience for children. There could be danger involved when the tide came in if the boys went to far out

We have little information about theatrical troupes at this time. We know they existed in the Tudor era as Shakespeare's and other historicl plays were performed by theatrical troupes. We are not sure just when they first appeared. We suspect that such troupes may have evolved out of the groups performing medieval passion plays. From the beginning boys were important in these troupes as they not only played the youthful male parts, but those of girls and women as well. Thus a substantial part of the characters were played by boys. I'm not sure when girls first began to perform in plays, perhaps not until the 19th century. e note an acting troupe called Casey's Court in the early 19th century made up of boys and young men. One of the boys is Charlie Chaplin. I am nor entirely sure what a boys' acting troupe would do at the time.

Usual tasks were scaring off birds, tending animals, driving the plough and assisting the “carter” or cowman. Small farms employed very few servants and only a limited seasonal agricultural labour when necessary. During harvest the crop-picking work was carried out by all members of the family, including the children and usually unwaged at that.

Navigate the Boys' Historical Clothing Web Site:

[Return to the Main English working boys page]

[Return to the Main activities page]

[Introduction]

[Activities]

[Biographies]

[Chronology]

[Clothing styles]

[Countries]

[Bibliographies]

[Contributions]

[Essays]

[FAQs]

[Glossaries]

[Images]

[Links]

[Registration]

[Tools]

[Boys' Clothing Home]