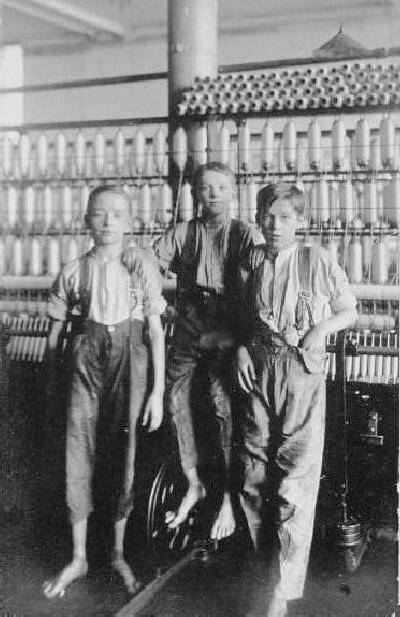

Figure 1.--These boys worked at a mill in Bolton. The photograph is undated, but was taken before World War I, probably about 1905-10. Bolton is a city in the industrial midlands where the Industrial Revolution began. |

|

England as far as we know was the first country to address the problm of child labor. This is understandable as it was in England that the Industrial Revolution began. Child and women workers played a major role in the Industrial Revolution. Charles Dickens had a major role in prmoting the movement to limit child labor. Parlimentary investigations exposed the abuses, but influential English capitalists committed to laiisez faire government claimed that governmental restrictions were an infringement of their rights. Here Dickens and news accounts of abuses gradually swung public opinion to governmental action to protect children. Finally Parliament began limiting child labor, the initial laws were very minor restrictions.

The rural poor with few exceptions did not own land in England. The industrial Revolution began (mid-18th century). At the time, the land was mostly owned by aristocrats controlling large estates and byh the gentry with smaller estates. The landed gentry, or the gentry, is a historical British social class of landowners who could live from rental income, often she rferred to as the gentry, or at least had a country estate. This was normally much smller than the estates owned by the aristocracy. The landholdings of the gentry were significantly expanded during the regin of King Henry VIII when he disbanded the monastaries. The before the Industrial Revolution wax tht the great buklj of the popultion lived in the coiuntry and was involved in agriculture. And the people actully working the land did not own it. This was a very different situation than what transpired in France after the Revolution (1789). As a result of the Revolution, the French peasantry gained control of the land they had been working. This has been described as the greast gift of the Revolution. Too often, when assesing the English Industrial Revolution and the condition of urban workers, the idea is perpetrated by Marxist authors that workers in the countryside read idelic lives. This was not the case. Rural workers were pooly paid and lived hard lives of drugery and poverty. This is not to say that conditions in the city for the poor were not terrible. It is to say that the Industrial Revolution generated great wealth and many more people benefitted nd were better off than was the case before industrialzation. A substantial middle class was created which unlike the aristocracy supported a range of reform movements. They read the Dikensian stories and were moved, supporting reform movements . The result was the British weokers were the best paid in Europe.

Laissez faire economics is an economic and political system in which government intervenes as little as possible in the economic system. It was a reaction to the mercantilist system in which government played a central role in a country's economic life. Political economists who argued that for the state to interfere with the rights of parents to decide what they should do with their own children was a gross infringement of individual liberty. Backing the economists were the employers who argued that any restrictions limiting hours or other controls on their workforce would raise wage bills, increase prices, reduce demand and lead to the economic ruin of themselves and the country. Influential English capitalists committed to laissez faire government claimed that governmental restrictions were an infringement of their rights. As the system developed in the 19th century it mean that government did not restrict economic activity and the abuse of working people, but that industrialists relied heavily on government to restrict efforts by working people to form unions to achieve some parity with owners in negotiations over wages and working conditions.

The Industrial Revolution in the process of revolutionizing the British economy impaired the livilhood of many workers. This disrupted family life creating many homless children, many of which could be found on city streets.

Currently we only have a page on English street children. We believe that this was a problem throughout Europe, America and Canada, and other countries. We are not sure to what extent the problem in England compared to other countries. As the Industrial Revolution appeard first in England, the problem with abandoned children may have appeared first in Britain.The availavility of inforamion suggests that it may have been greater, but perhaps the English just publicized it more in an effort to address the problem.

The literature on English orphanages and work houses is legion. Of course most of our concept of English orphanges comes to us from the bleak descriptions Charles Dickens provides in Oliver Twist. As bad as conditions were in 19th century English institutions, it should be remembered that these were some of the first attempts to deal with the problems of poverty. The Victorians viewd these efforts as Christian charity. Other strongly held Victorian values resulted in the creation of institutions that were in fact as bleak as Dickens described. Many Victorians saw poverty as a lack of effort and a result of a flawed character. Others felt that it was more charitable not to intervene and that Government action would simply foster a debter class that would create even more indigents.

Parish authorities in England during the 18th and 19th centuries strove to find suitable employment for child paupers and orphans; the aim was to remove the need to support them on the local �poor rate�. Orphanages and poor houses began in effect to rent the children out to employers. This not only reduced the financial responsibility of the parishes, but actually geberated income. The children involved were not aware of the meaning of the contracts they signed. Most found that wages, if paid at all, were low; apprentices worked for little more than their board and lodgings. The training received was minimal � it did not fit them for a future job in adult life. The contracts usually bound the children until they were of age and then discarded them in favour of more young recruits. Discipline was maintained via a combination of fines, solitary confinement, physical punishment and reductions in their diet.

Social commentators, towards the end of the 18th century, started to express concerns about potential abuses involved in reliance on child labour.

Children in the 18th and 19th children were involved throught the British economy, including many of the most important industries. They along with women were employed in both mines and. Often they were given some of the most dangerous jobs. The age of the boys depended on the size of the mineshafts: wide ones enabled boys aged 14�18 to work but thinner ones necessitated using boys as young as 7 until the 1842 Mines and Collieries Act banned the use of boys aged under 10 below ground. In the cotton industry, adult workers were paid on a piece-basis i.e. according to the amount they produced. A system of sub-contracting existed which meant that many child workers, instead of being directly employed by the manufacturer, were employed by adults and paid out of their wages. In the 1830s the use of 3 children per spinner had become the norm. Typical tasks were: 'Scavening' - Children oiled the machinery and wiped down twice daily as the machines powered down for the midday break and evening closedown. Hawkers sold anything from matches and ice creams to flowers and hot peas. Some were knife sharpeners, others organ grinders. One regular job was as a 'knocker-up' i.e. to walk along the street, early in the morning, carrying a long stick with which to hit the bedroom windows to wake people up in time for work. The most common street trade was selling newspapers. The clerk and Post Office telegraph boy appeared to be promised job security and many parents considered them as being in respectable employment. Unfortunately clerks were little more than messenger boys and cleaners; furthermore they usually earned less than mill operatives did. Shop boys were used to mind pavement displays from being stolen or act as door-boys for high-class stores. Some even served the customers. At seaside resorts boys made ice creams or carried bags for tourists at railway stations. Local children played truant from school to work for the summer, usually with their parents� permission, because they had to compete with migrant boys from the cities also looking for work. Usual tasks were scaring off birds, tending animals, driving the plough and assisting the 'carter' or cowman. Small farms employed very few servants and only a limited seasonal agricultural labour when necessary.

Some local parishes gradually started to attempt to protect the wellbeing of the children they apprenticed so far away from their homes. Abuses uncovered led to action by Parliament at the national level. The 1812 Health and Morals of Apprentices Act limited hours to 12 per day and banned night working for apprentices from 1804 onwards. Thereafter the 1819 Factory Act prohibited children under 9 from working in cotton mills and limited the work of those aged under 16 to 12 hours per day, 9 hours on Saturday, exclusive of meal times. The 1831 Factory Act extended the law to those aged up to 18.

Charles Dickens, who was forced to work as a child himself, had a major role in exposing the impact on children and prmoting the movement to limit child labor. Charles Dickens is regarded by many as the greatest novelist in the English language. He is especially notable for the wonderfully diverse chracters he created. Among them are some of the most famous boy characters in literary history. Oliver Twist was in fact the first boy character to be the main character of a novel. Dickens authored 15 major novels and numerous short stories and articles. Oliver David, and Pip are the best known, but many other boys and girls populate his novels. The most memorable are those wounded and in some cases destroyed by poverty, in part because of his boyhood experiences. Oliver Twist and David Copperfield are the two child characters most associated with the Industrial Revolution and child labor. The epitat on his tombstone in Poet's Corner, Westminster Abbey reads: "He was a sympathiser to the poor, the suffering, and the oppressed; and by his death, one of England's greatest writers is lost to the world".

Parlimentary investigations exposed the abuses.

Children received no special protection under British law until the Industrial Revolution. It was Britain that invented the Industrial Revolution. And it was Britain that began to protect working children. Too often the abuses of child labor is blamed on capitalism and industry. We see texts like "When the Industrial Revolution began, industrialists used children as a workforce," suggesting that industrialists invented child labor.But children for millennia worked including in abusive circumstances. Children were an important part of the work force in all societies. Laws to protect children began to be enacted, but only in a few capitalist countries where the Industrial Revolution was unfolding. Elsewhere and to this day, child labor continues. This only began to change and only in a few countries (19th century). Laws to protect children began to be enacted first in Britain. Young children were working very long hours in workplaces where conditions were often horrible. The basic act was prohibited child workers under 9 years of age.The question rarely asked is -- why? Child labor was nothing new. The answer is unclear. Factory was perceived as more abusive than agricultural work. Perhaps more dangerous, but we are not at all sure it was more abusive. A factor often ignored is the growth of the middle class,generated by the Industrial Revolution, which was more concerned with social issues. Attitudes toward childhood were changing. And mass media was developing bringing abuses to public attention. Attitudes toward childhood were changing. Charles Dickens published David Copperfield (1859-60) to great public acclaim. Factory abuses were very real and more visible than what occurred in isolated rural areas. Thee were no compulsiry school attendance laws. News accounts of abuses gradually swung public opinion to governmental action to protect children. Finally Parliament began limiting child labor, the initial laws were very minor restrictions. The first such law was the Factory Act (1833). It banned children under 9 years old from working in factories. It limited hours, and required some schooling, gradually setting precedents for modern protections against exploitation, as seen in legislation like the Mines Act (1842). .Two more Factory Acts followed (1844 and 47). The Factory Act of 1844 regulated the relay system. Some factory

owners had avoided limits on the working day for children by developing a relay system. The children might work from 5:00 am to noon and then begin to work again at 1:00 pm under the guise of a new shift. While the 1844 Act regulated this abuse, it granhted factory owners the right to employ children at age 8 insttead of the previous 9 year old limit, his opened up a new supply of potential workers. [Wilson, p. 53.] There were some concessions granted factory owners, but the overall arc of the legislation was to prorect children. These laws limited the hours children could be worked. The Factory Act of 1844 regulated the relay system. Some factory owners had avoided limits on the working day for children by developing a relay system. The children might work from 5:00 am to noon and then begin to work again at 1:00 pm under the guise of a new shift. While the 1844 Act regulated this abuse, it granted factory owners the right to employ children at age 8 instead of the previous 9 year old limit, his opened up a new supply of potential workers. 【Wilson, p. 53. 】 Numerous Parliamentary Acts followed to further protect children over time. The Children Act (1908) prohibited children under the age of 14 years from entering pubs.

Factory workers were the first children for whom some education was compulsory, but amongst the last required to attend school full-time up to age 14. The 1844 Factory Act tried to balance the needs of education & industry. Children employed in textile factories (not silk), aged 8-13, were allowed to work: either 10 hours per day on 3 days per week, attending school full-time for the alternating days; or 6 hours per day, every working day (i.e. 6 days a week), while attending school for 3 hours each day except Saturday.

In order to work, half-timers had to produce a certificate of school attendance for the preceding week. Any shortfall in stipulated school hours had to be made up before paid work could be allowed. Thus there was a very real incentive to maintain good attendance and, since there was no requirement to send children who did not work to school, it was possible that children might only have started attending when they began in the mills in order to allow them to work. A popular chant of children was 'No School, no mill; no mill, no money'. For these reasons, there were discrepancies in the ages children actually went half time; if they could be passed off as older, they were. The half-time system in textile factories soon came to be considered as the ideal model to be applied to other workplaces that employed children; it combined the benefits of education with early training for work. Half-timers also performed better at school than full-timers did because the regularity of their attendance compensated for the fewer hours. Therefore other occupations and industries adopted the half-time system: printing in 1845, bleaching & dyeing in 1860, lace in 1861, pottery, making matches, percussion caps and fustian cutting in 1864. The 1867 Factory Act extended it to virtually all non-textile factories and workshops. The 1874 Factory Act raised the minimum age of �half-time� employment to 10.

Therefore the 1876 Education Act made full-time education compulsory to the age of 10 years and stipulated that children aged 10 - 13 could be employed only if they had attained certain standards of proficiency in reading, writing and arithmetic, or had achieved a specified number of attendances at school. The 1891 Factory Act raised the minimum age for employment in factories to 11. The 1893 Education Act raised the school leaving age to 11; this changed from 1st January 1900 to age 12. Photograph Number 3 Dennis, shows a poster from 1900 outlining the new regulations in Bury, Lancashire. Finally the 1918 Education Act abolished all partial exemptions and established compulsory, full-time schooling, until a child's 14th birthday.

A number of socially concious photographers in America and Europe helped to highlight working conditions for children and women. These images played a major role in legistaltion to protect the vulnerable groups. I was aware of still photographers. We have since learned that in England and France there were also early documentaries, so called "Factory Gate Films. I do not know of any similar American films. Apparently Edwardian film makers made news reels at the turn of the 20th century. A lot of their films have been discovered in the cellar of their former studio in Blackburn Lancashire. The British Film Institute have renovated these. Some stills are available on their web site. The English film makers were Mitchell and Kenyon. The French Lumi�re Brothers were apparently the first to shoot these films and show them to fee paying audiences (1895). One was named the "Sortie de l'Usine". The film was taken at the factory gates in Lyon. The goal of the film makers was more technical than social. They wanted ti show how film could record movement and the factory gate when the whistkled sounded offered a good opportunity to film a large group of people moving. Mitchell and Kenyon shot their films in England and there were other early English film makers shooting at the factory gate. Cecil Hepworth filmed in southern Enhland.

Reed, Lawrence W. "Child labor and the British industrial revolution," Liberty Haven, site accessed August 3, 2003.

Wilson, A.N. The Victorians (W.W. Norton & Co.: New York, 1993), 724p.

Navigate the Boys' Historical Clothing Web Site:

[Return to the Main working boys clothing page]

[Return to the Main activities page]

[Introduction]

[Activities]

[Biographies]

[Chronology]

[Clothing styles]

[Countries]

[Bibliographies]

[Contributions]

[Essays]

[FAQs]

[Glossaries]

[Images]

[Links]

[Registration]

[Tools]

[Boys' Clothing Home]